Like all political and social movements, environmentalism is a product of the group interests and perspectives that are represented in its constituencies. While environmental activism over the course of centuries has involved many different people and struggles, the popular image of “environmentalism” is still closely tied to affluent white suburbanites. This stereotype is not completely unfounded: historically, environmentalism has in fact amplified some voices over others. A focus on environmental justice requires considering how certain perspectives have come to be the dominant ones, and advocating for a more inclusive understanding of how humans and the natural world are connected.

Concord Junction, Mass.

George E. Norris

1893

Leventhal Map & Education Center

Henry David Thoreau’s 1854 book Walden; or, Life in the Woods is often considered one of the original texts of American environmentalism. The book’s popularity in the twentieth century made solitary retreat one of the hallmarks of experiencing “nature” firsthand. Thoreau’s Concord, however, was actually a busy community, and Thoreau would often walk less than two miles back into town to visit friends and family. This 1893 view shows Concord Junction (now West Concord) about three miles from Walden Pond. In the foreground is the Massachusetts Correctional Institution, at the time called the Massachusetts Reformatory, which opened in 1878. The same rustic landscape in which Thoreau wrote about life in the woods was also believed to have a salubrious effect on prisoners. Today, incarcerated people often face some of the most degraded environmental conditions of anywhere in the country.

Panoramic View of the Yosemite National Park, California

John H. Renshawe; U.S. Geological Survey

ca. 1914

Leventhal Map & Education Center

Motor Routes that Intersect the Bay Circuit

Trustees of Reservations

ca. 1930

Leventhal Map & Education Center

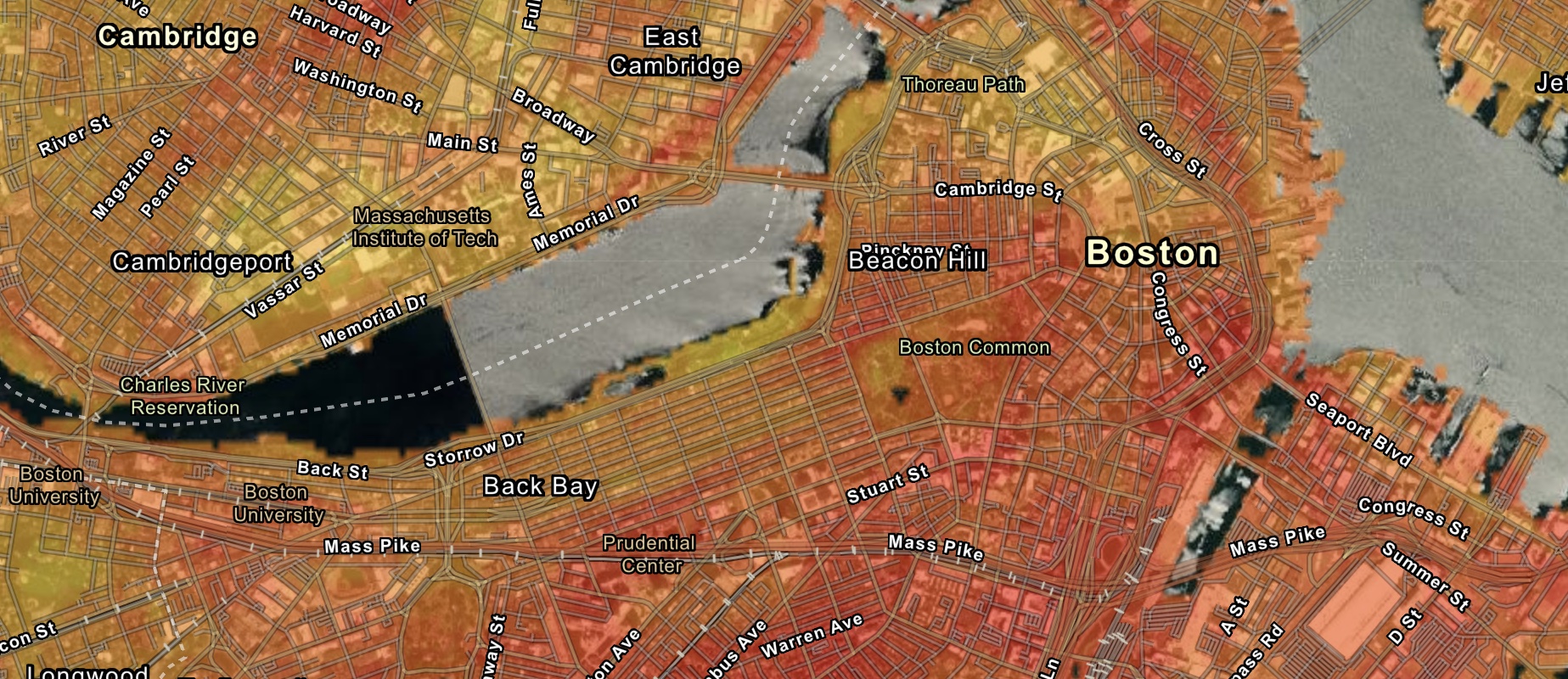

Protecting public space in the name of the people is an important goal for democratic societies. Frederick Law Olmsted, Sr., was one of the first to propose that the Yosemite Valley should be held in public trust, so that people of all social classes could enjoy joint ownership of such stunning natural beauty. Nearer to Boston, the proposed Bay Circuit greenbelt offered an opportunity to create green space easily accessible to city dwellers. In both these and many other cases of land protection, these democratic aspirations also obscured exclusions in who counted as part of the “public.” When Yosemite became a park, it meant that the indigenous Miwok peoples’ lifeways were permanently disrupted. The Bay Circuit map’s emphasis on automobile routes suggests that access to these spaces was primarily oriented towards those with cars, and, in later years, the green spaces around the city’s outer periphery would become closely linked with elite suburbanization.

Dr. Robert Bullard

Environmental Autonomy

Dr. Robert Bullard, often called the father of environmental justice, was a lead organizer of the First National People of Color Environmental Leadership Summit in 1991. While white environmentalists often used their networks to set agendas regarding human impact on the environment, people of color, the most affected by environmental dangers, were usually left out of the process. In response, the summit’s principles stated that “Environmental Justice demands the right to participate as equal partners at every level of decision-making, including needs assessment, planning, implementation, enforcement and evaluation.”

“… people most impacted by environmental challenges must speak for themselves and must be in the room when decisions are being made. And that we must develop the kinds of research, the kinds of empowerment tools, so that we can speak for ourselves and not allow others to go to Washington or go wherever and speak for us.”