Building roads is one of the most expensive things that local governments in the United States do: both in terms of dollars spent as well as in terms of the area needed for these massive projects. But automobile transportation is also one of the most polluting and inefficient forms of transportation, and the consequences have been tragic for many cities, with the burdens of the paved-over environment falling most dramatically on the communities least able to resist such plans.

“Our findings are consistent with other studies that have also demonstrated the existence of persistent racial inequities in exposure to ambient air pollution across Massachusetts. The overlapping spatial patterns of pollution and residents of color is not merely a quirk of geography.”

— Conor Gately and Tim Reardon, “Racial Disparities in the Proximity to Vehicle Air Pollution in the MAPC Region,” Massachusetts Metropolitan Area Planning Council, May 2020

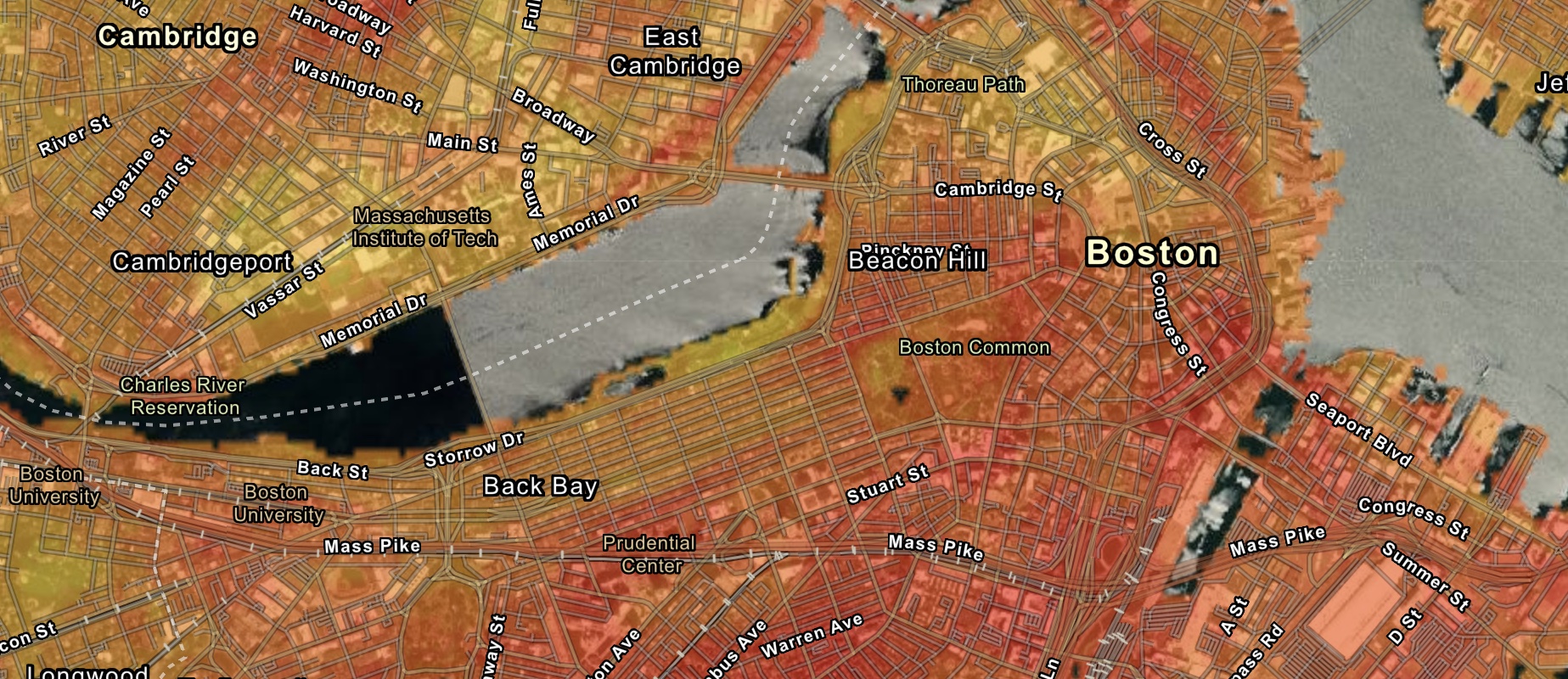

Master Highway Plan Metropolitan Boston Showing the Massachusetts Turnpike, Route 128 (Circumferential Highway), Boston Central Artery, and Planned System of Expressways

Cabot, Cabot & Forbes Co.

1961

Leventhal Map & Education Center

Cabot, Cabot, and Forbes, a major development firm, commissioned a series of maps in the 1950s and 60s to show off the urban region’s economic development, emphasizing the new highway construction connecting downtown to new investment opportunities in the suburbs. Dashed green lines show the routes of planned highways, while the red areas show industrial parks and malls around the Route 128 corridor. The massive shift to automobility in the decades after World War II had severe social and environmental consequences, for it allowed both white residents and their investments to flee the cities, leaving poorer communities literally at the end of their tailpipes.

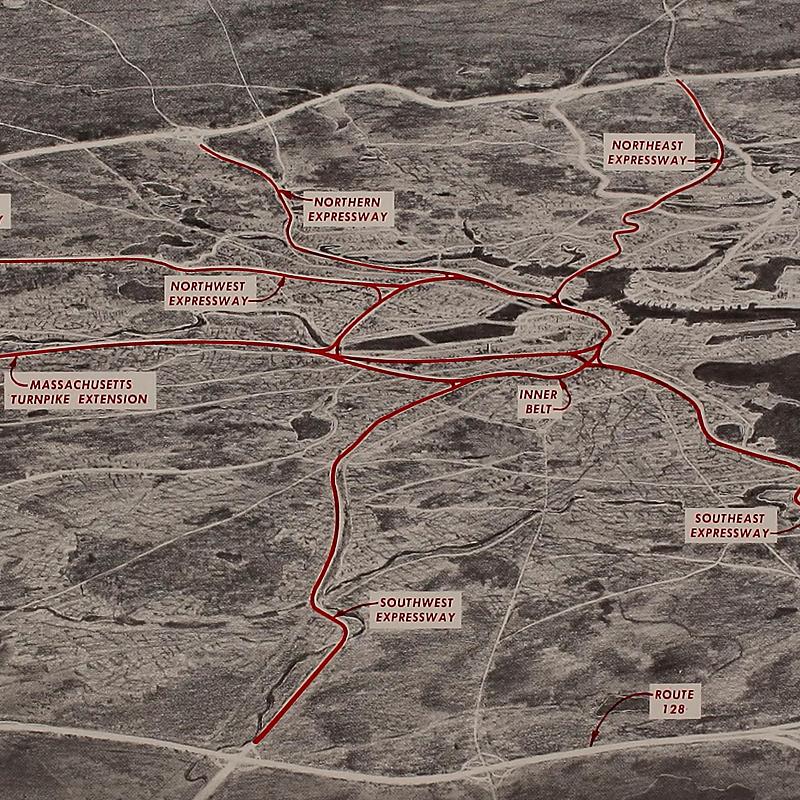

Inner Belt and Expressway System, Boston Metropolitan Area

Massachusetts Department of Public Works; United States Bureau of Public Roads; Hayden, Harding & Buchanan, Inc.; Charles A. Maguire & Associates

1962

Leventhal Map & Education Center

The development of highway networks had the support of both government officials and business leaders who hoped it would spur economic revitalization. People who lived in the areas slated for highway demolition, however, began to fight back, and in the decades that followed a major citizen-led movement against further highway development would become one of the forerunners of environmental justice activism in Massachusetts. Protest and organizing was successful at stopping harmful government action, but forcing positive change has turned out to be more difficult. Although the state announced a moratorium in 1970 on new highway construction around Boston, securing investments in greener amenities for these areas continues to be the focus of organizing efforts.

Lily Xie

Artist

Photo credit: Tarik Bartel

Air, Art and Community

Truncated in the 1950s and 60s by the construction of the Southeast Expressway (I-93) and Mass Pike connector, the Chinatown neighborhood of Boston experiences some of the highest concentrations of Traffic-Related Air Pollution (TRAP) in Massachusetts, threatening the health of residents. Over the last 20 years, academic institutions and Chinatown community partners have worked together to address TRAP by supporting legislation, arguing for affordable public transit, advocating for air filters in buildings and homes, and participating in public art projects to raise awareness. In 2021, a multimedia art project titled Washing (洗作) created by Lily Xie, Maggie Chen, Charlene Huang, Chu Huang, and Dianyvet Serrano in collaboration with Asian Community Development Corporation (ACDC) brought together projected images and resident voices in an outdoor installation to tell stories of the highways’ effects on the neighborhood.

“When our team was designing this project, we really emphasized the need for repair. In Chinatown, when it comes to repairing the effect of the highways, there is so much more than air—the highways also destroyed large sections of the neighborhood, displaced people who were never able to come back, made a rupture that is very much still felt today. Our project tries to illustrate how that is felt in people’s bodies, and the way that they live their lives. What does repair look like, in this context?

We saw public art as a way to literally amplify people’s voices. We used video projections to reveal the layers of history on Hudson Street—tying together the people who used to live there and were displaced when the highway was built, all the current residents who live with the effects of the highway, the activism in Chinatown that has afforded residents better lives, and the strength of the community.”