Essays

Of Odors and Esplanades

Here’s a riddle for you. What has no shape, takes no form, and greatly impacts our experiences of urban space? Is it sunlight? Noise? Greenhouse gas emissions? Yes, yes, yes: all of these ephemeral qualities make for excellent answers (and they also feature prominently in our upcoming exhibition, More or Less in Common). They shape how we move through and engage with cities, even though we don’t see, feel, or touch them in the same way we might touch the dirt in a park or the bricks on a building. Today, I want to focus on one of these ephemeral qualities in particular: smell.

Exhibition Prospectus

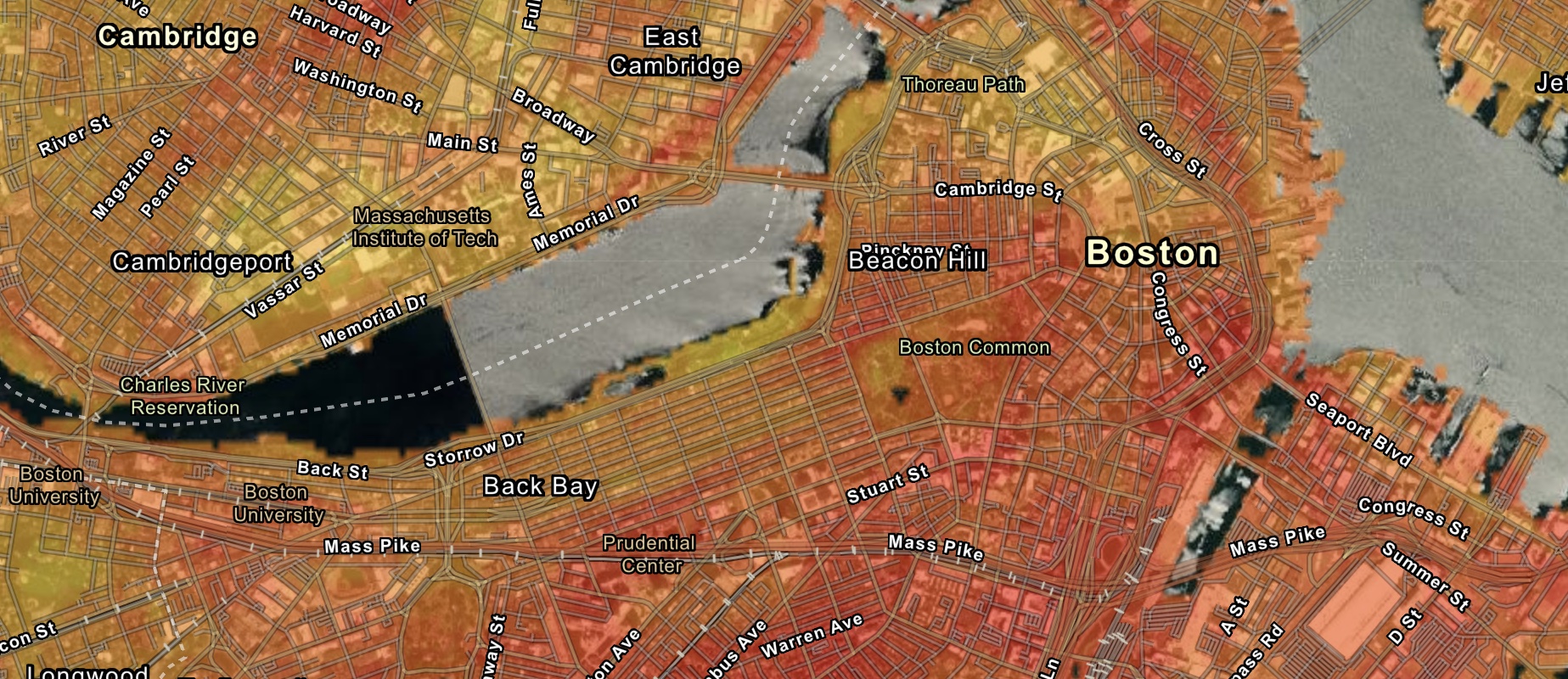

For those who have come to think of environmental concerns like pollution control and social issues like racism as distinct and disconnected challenges, the term “environmental racism” might seem at first like an unfamiliar conjunction. Even before the origins of the modern environmentalist movement in the 1960s, efforts to protect and improve the human landscape have often been cast in terms of universal benefit. A well-kept public park, a river free of toxic chemicals, or a stable global climate all seem like amenities that can be shared by all, free of discrimination by race, class, ethnicity, nationality, or gender.

In reality, however, the advantages of a well-protected environment—and conversely, the hazards of a damaged one—have rarely been evenly spread.