Enbridge is a multinational gas pipeline company currently moving fracked natural gas from Pennsylvania to Eastern Canada. The company asserts that the Weymouth compressor, sited less than ten miles south from where you stand, is needed to process the gas as it continues its journey. Unlike most compressor stations, however, the compressor in Weymouth is bookended by densely-settled environmental justice communities, communities that continue to bear a disproportionate burden from industrial infrastructure and are the most vulnerable to its negative impacts. The state identifies areas as environmental justice communities by referencing data on income, race and level of English proficiency.

Compressor stations release a number of toxic substances, most notably in “blowdowns” when pressure is released by venting large amounts of untreated natural gas into the air. Despite a statement by the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission’s chairman in January 2022 that regulators “should never have approved” the compressor, the commission did not move to revoke its authorization. Concerned South Shore residents, environmental scientists and local politicians are looking for ways to shut down the compressor in what is already an environmentally overburdened region of the state, an area called a “sacrifice zone,” so called because new potentially dangerous facilities are often sited in areas in which other polluting and dangerous facilities already exist.

Rev. Betsy J. Sowers

Minister for Earth Justice at Old Cambridge Baptist Church and member of Fore River Residents Against the Compressor Station (FRRACS)

Too Close For Comfort

Reverend Betsy Sowers is Minister for Earth Justice at Old Cambridge Baptist Church and a board member at Fore River Residents Against the Compressor Station (FRRACS). Betsy represents the church through involvement in both faith-based and secular climate justice organizations and actions. She also helps church members and friends of the congregation connect the dots between Earth justice and related justice concerns, especially racial, economic, gender, and immigration/refugee justice.

Even before the compressor station was built, people in the Fore River Basin were coping with their children and other family members having cancer, respiratory and neurological diseases caused by the other toxic emitters in the area. With the addition of the compressor, fears for their health have increased, and fear for their safety has been added, because the compressor is explosive and there are many people who live in the blast zone. COVID has added another layer of anxiety, because we’ve learned that the virus can ride on particulate matter, and that people in environmental justice communities whose respiratory systems are already compromised by pollution are more susceptible to it.

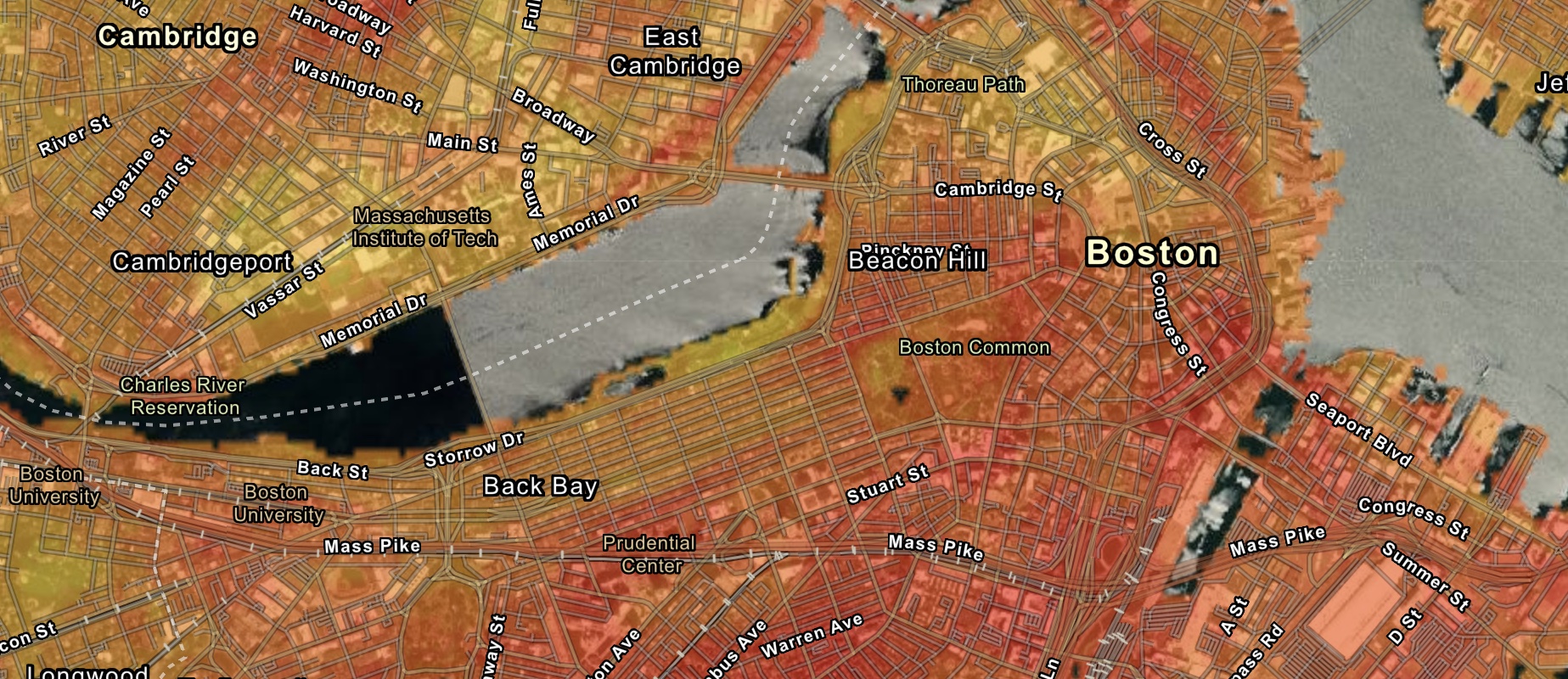

These are very personal, very intimate impacts on people’s physical health, their mental health, their level of anxiety. So, weigh that in addition to the macro—the big maps, where you see how environmental injustice affects a whole region or whole groups of people—people of color, people of low wealth, people of limited English. It moves you when you learn about large groups of people who are impacted, but the enormity of the challenge can make it hard for folks to know what to do. But when it’s your neighbor who has a name and a face, or a neighbor’s kid who is suffering it really brings it home. It moves you to action.

Then you can take it from that very intimate place back to the largest map, and look at what ever-increasing pollution and projects like the Weymouth compressor are doing to our local environment, and our global environment, and our future—first to people in environmental justice communities, but inevitably to all of us, our children, grandchildren, and the precious, sacred web of life itself. Sometimes it’s that combination of understanding the enormity of the challenge, and experiencing it at the very personal level that lights the fire of change.