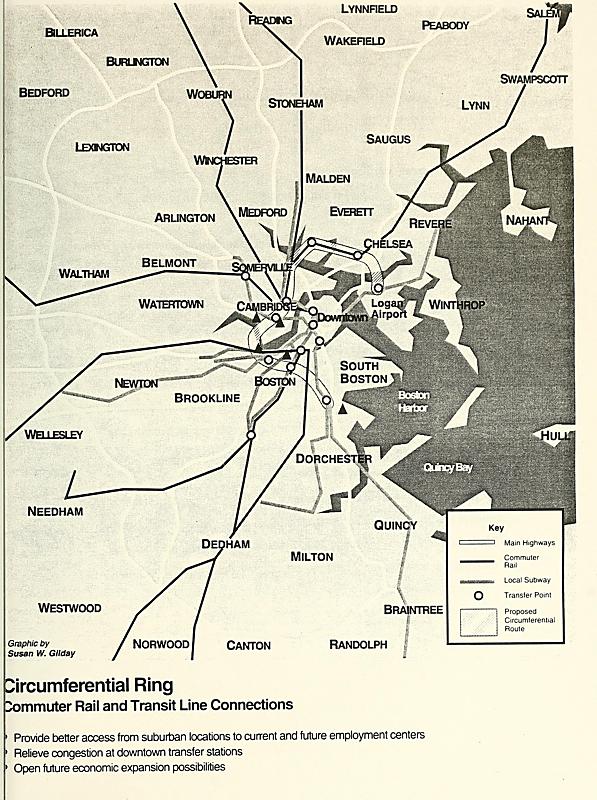

A Circumferential Route

UP1.1

Map of the Existing and Proposed Circumferential Thoroughfares of the District and Their Connections

Arthur A. Shurtleff [later Arthur A. Shurcliff]; Metropolitan Improvements Commission

1909

Mapping Boston Foundation

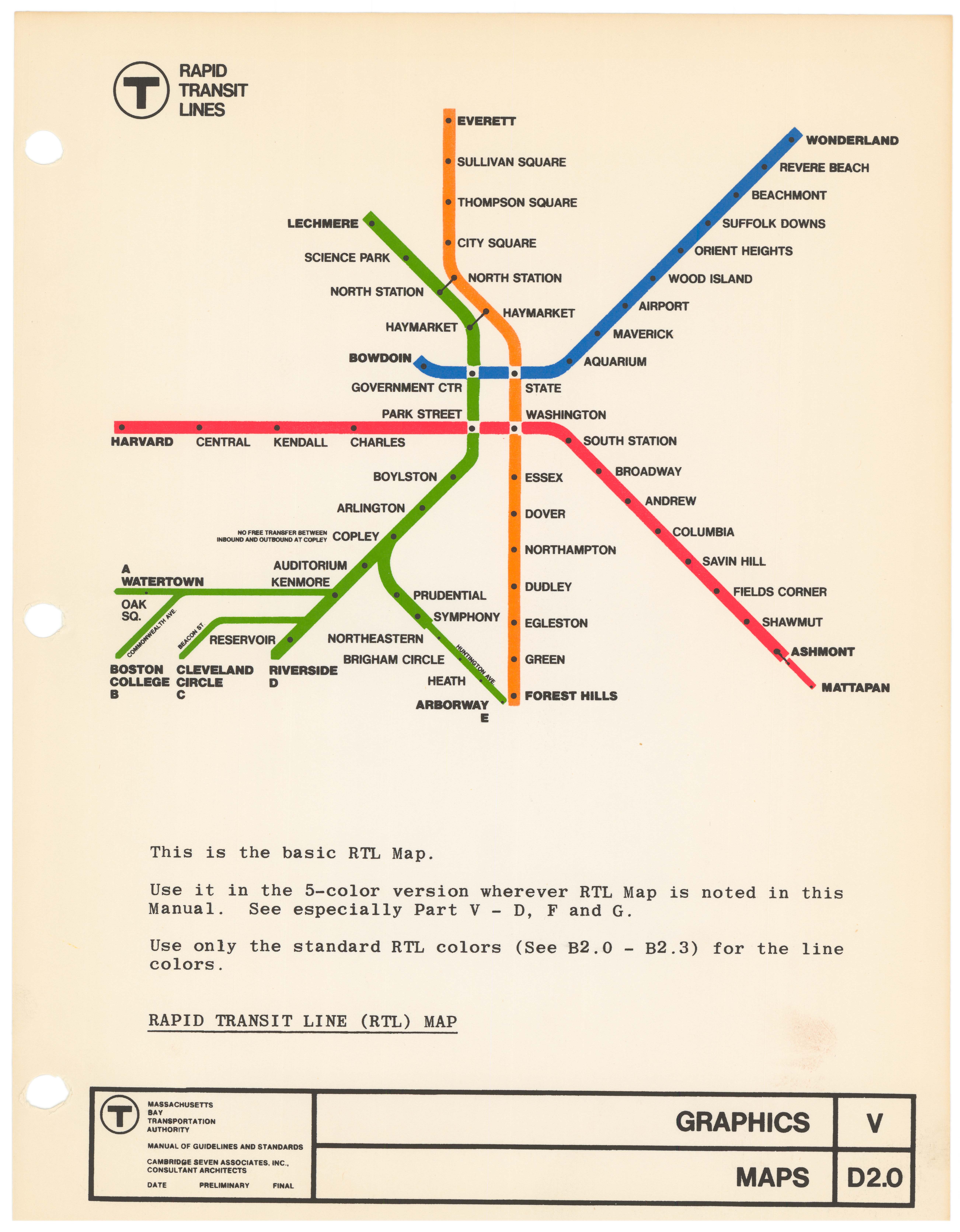

The original skeleton of the Boston region’s transit system was primarily oriented towards connecting the core of downtown Boston, where most jobs were found, to the areas around the city where many people lived in residential neighborhoods. This created a “hub and spokes” layout which is still in place today, with train lines converging in a tight core of four downtown transfer stations. As the city’s economic geography began to grow more complex, planners began to realize the need for circumferential connections that could link the spokes to one another via an urban ring. Arthur Shurtleff’s 1909 plan above, which focused primarily on surface roads, was among the first to emphasize the need for radial routes. Throughout the twentieth century, many proposals were floated for adding an urban ring to the public transit system, with particular emphasis on connections between the job-rich neighborhoods of Cambridge and the Longwood Medical Area. This 1995 map at right comes from a signing ceremony where a group of mayors committed to a plan for building a circumferential ring. Despite political and financial commitments, the only progress towards such a goal has been the addition of some additional bus service along this route.

UP1.2

“Circumferential Ring: Commuter Rail and Transit Connections,” from Circumferential Ring Regional Planning Compact Signing Ceremony

Susan W. Gilday

1995

Boston Public Library

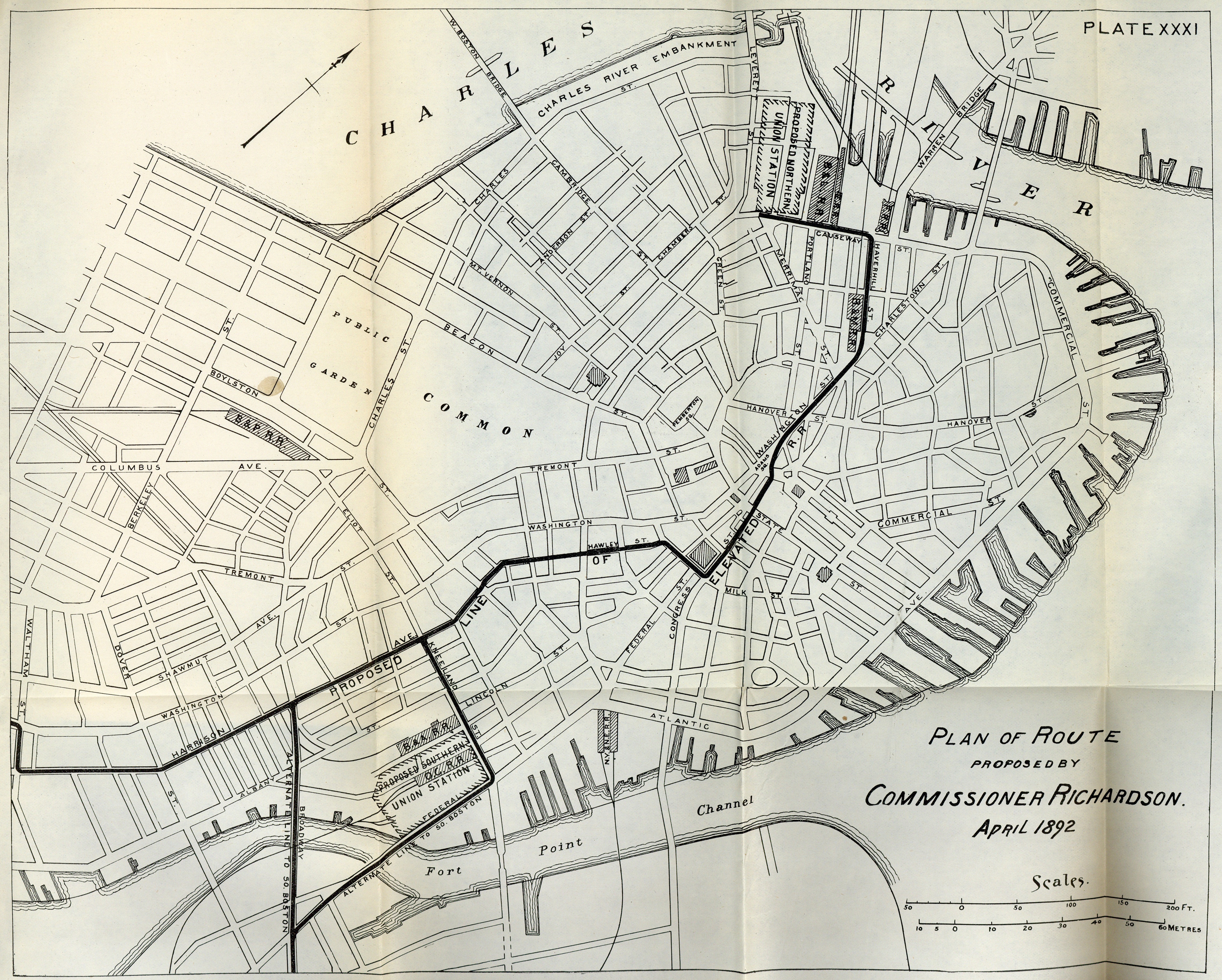

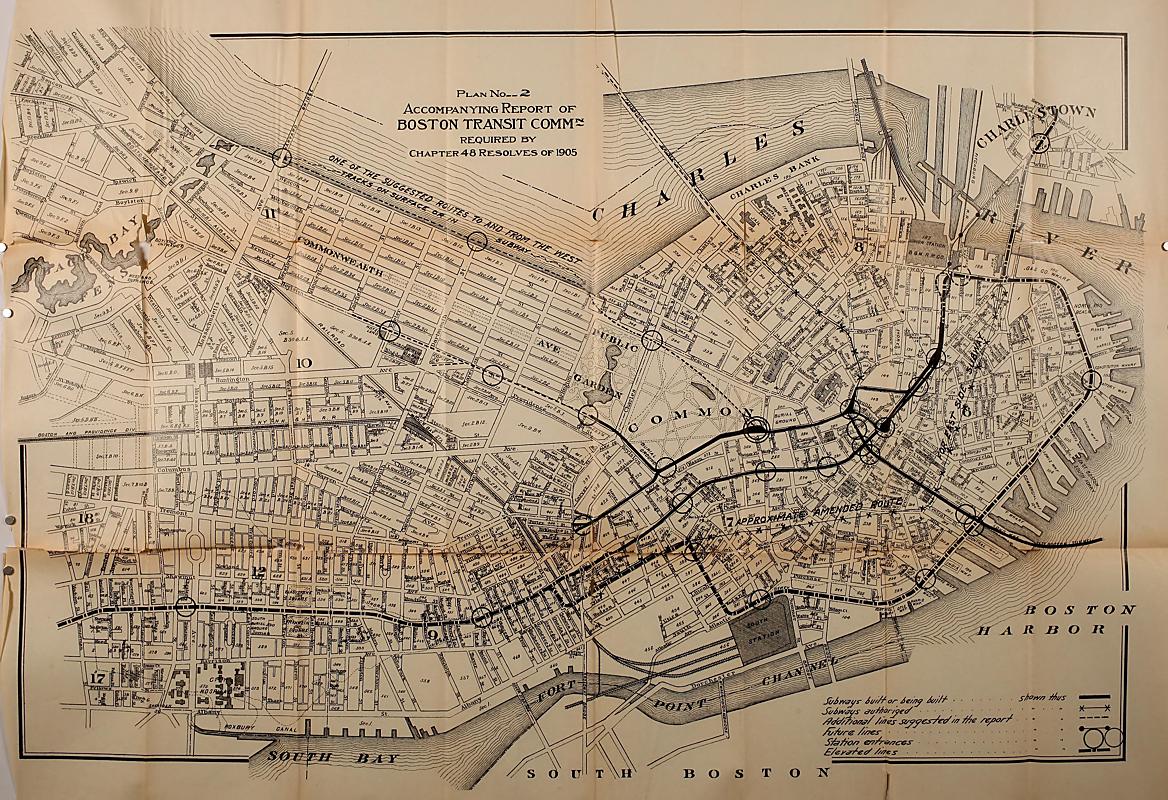

Meeting Red and Blue

UP2.1

“Plan No. 2,” from Twelfth Annual Report of the Boston Transit Commission, for the Year Ending June 30, 1906

Boston Transit Commission

1907

State Transportation Library of Massachusetts

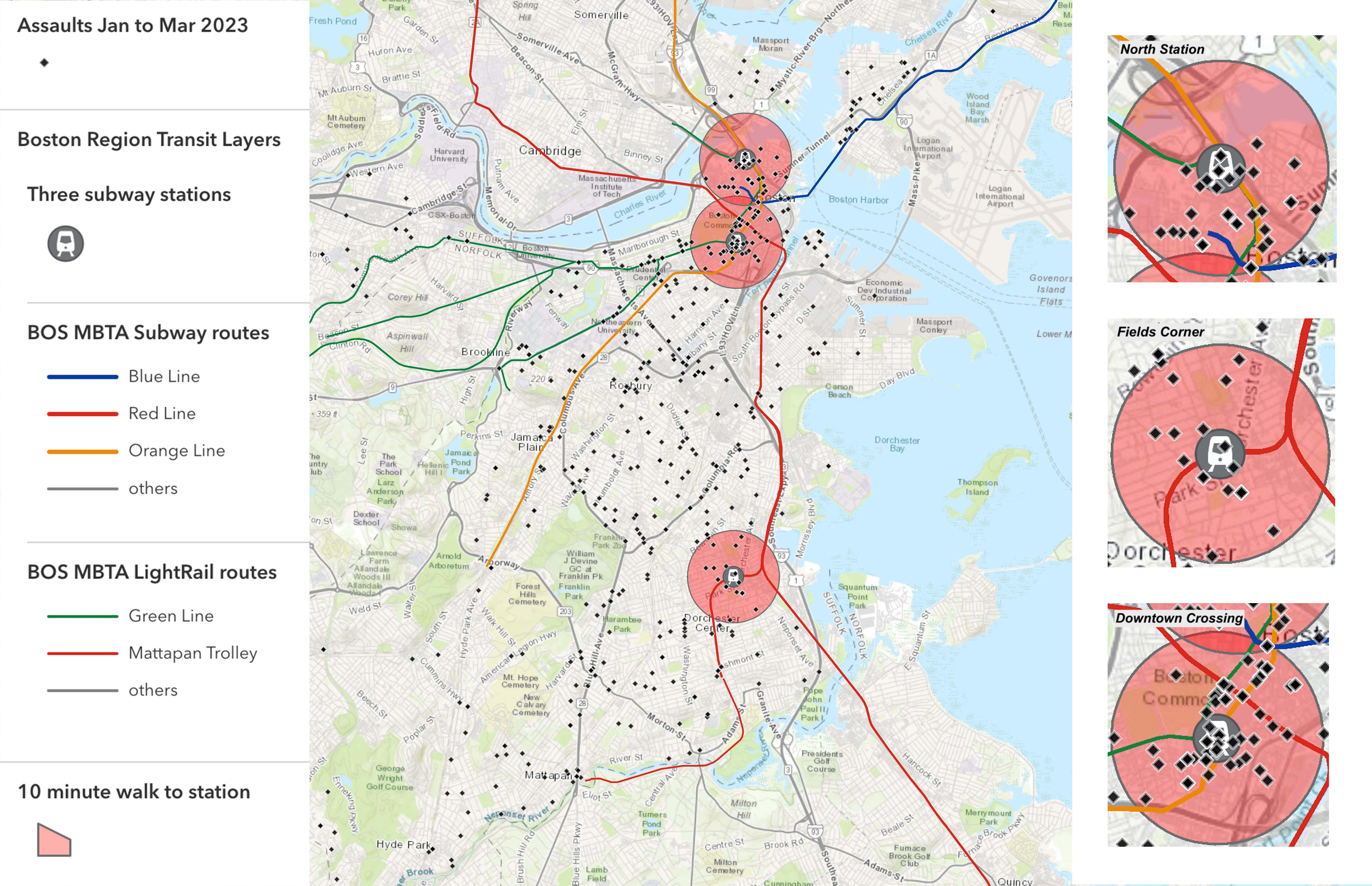

This 1906–1907 map above from the Boston Transit Commission depicts a period when the city was planning significant new expansions to its rapid transit network. Lines dotted with “X” symbols indicate “Subways Authorized,” and one of these lines runs between Scollay Square in downtown Boston, along Cambridge Street, connecting to the Cambridge subway at the Longfellow Bridge. (See the orange outline annotation, which has been added as an overlay.) As early as the 1890s, the legislature had already authorized tunneling under Cambridge Street so that the East Boston Tunnel could link to Cambridge trains. In 1909, the Boston Elevated Railway (BERy) chose instead to tunnel under Beacon Hill, connecting Cambridge trains to Park Street Station. Because of this decision, today the Red Line (the former Cambridge line) and the Blue Line (the former East Boston line) are the only two rapid transit lines in the system that do not have a direct connection to one another. In 1991, the state agreed to build a Red-Blue connector by 2011 as part of a lawsuit settlement, but the project was never brought to the construction phase. The project remains in planning today.

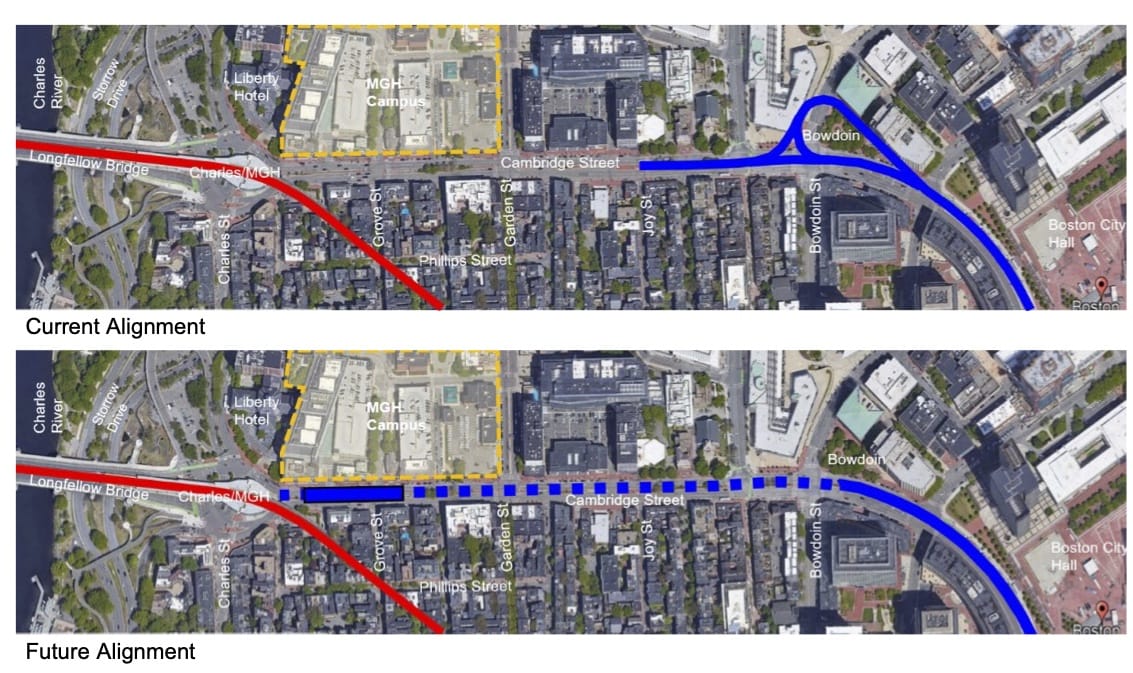

UP2.2

Red-Blue Connector Alignment

Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority

2021

Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority

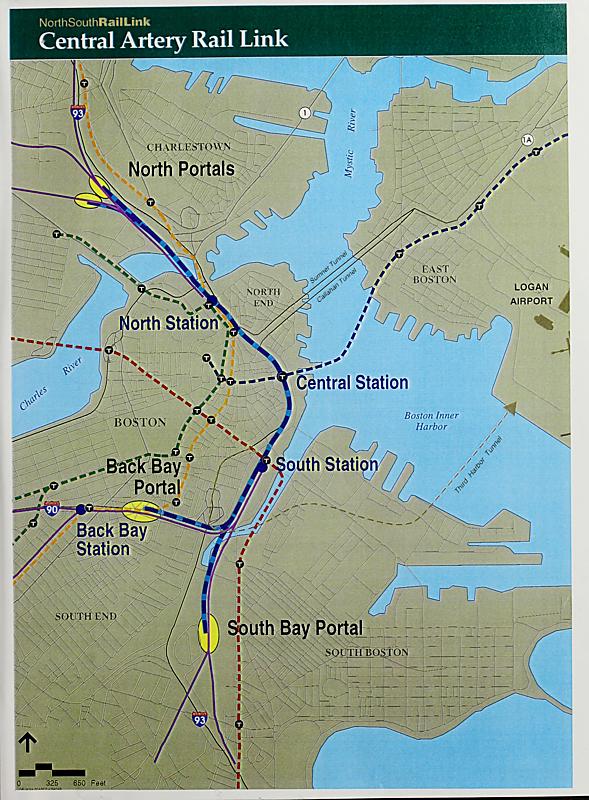

Connecting North and South

The consolidation of railroad terminals at North Station along Causeway Street and South Station along Summer Street brought all of Boston’s interurban railway traffic to these two major hubs. This 1911 souvenir promotional map above (printed by a soda, ice cream, and confectionery company) shows that it was once possible to connect directly between the two stations via the Atlantic Avenue elevated railway, depicted as red train tracks. A freight railway also ran along the same route, serving the busy industrial waterfront and its wharves. Today, it is not possible to travel between the two stations on a single ride, a shortcoming that planners have identified as one of the most significant gaps in Boston’s transit network. During the Central Artery project, better known as the “Big Dig,” plans were drawn up to connect the stations directly via a new underground rail link, which would not only close this gap in the rail network but also allow for more efficient passage of trains between the north and south halves of the MBTA’s commuter rail network. This 1994 map shows a proposed routing of tunnels and surface portals. Despite the massive amount of money spent on highway construction during the Big Dig, the North-South Link was not realized.

UP3.2

“Central Artery Rail Link,” from North South Rail Link Fact Sheet

Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority

1994

UMass Amherst Libraries

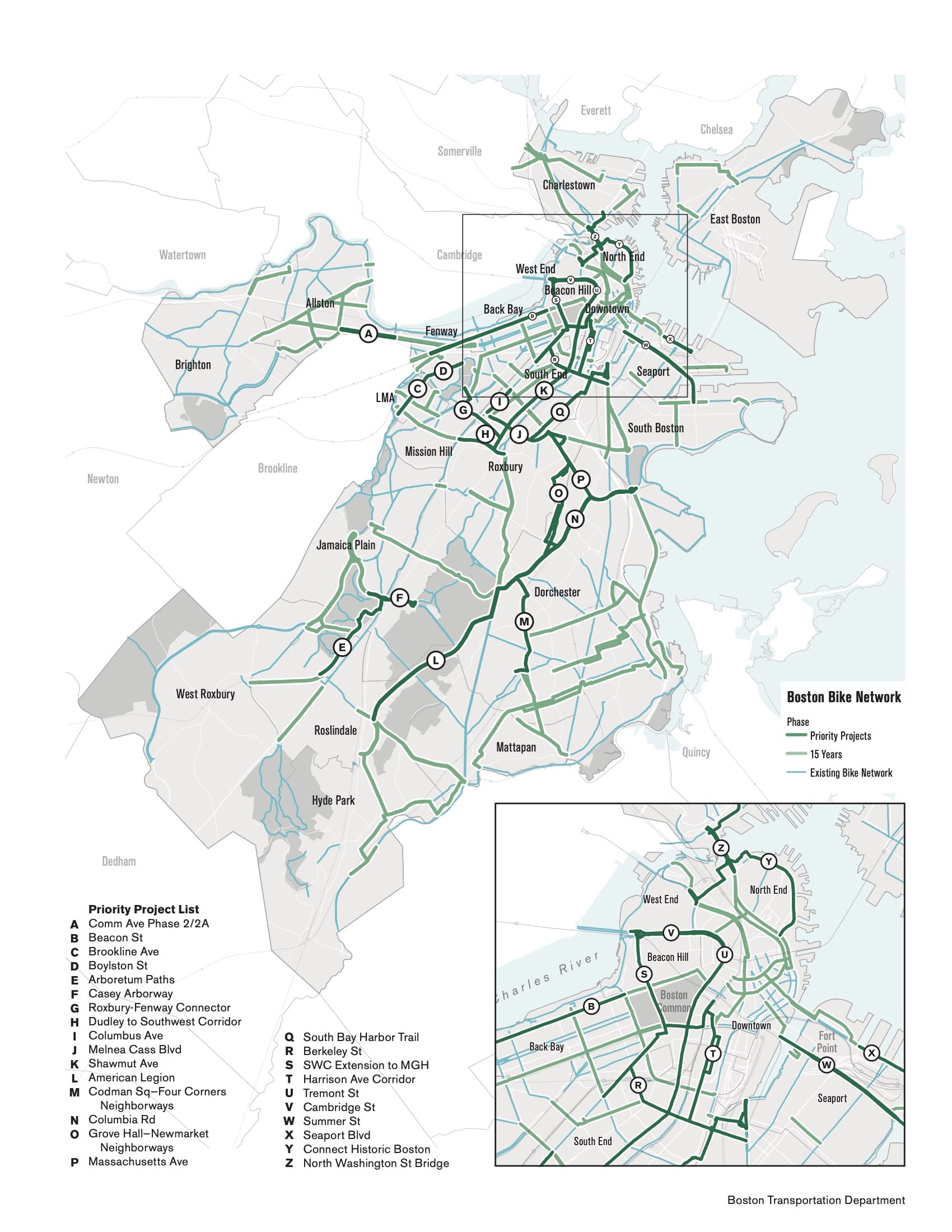

Pedaling Around Town

UP4.1

Road Map of the Boston District Showing the Metropolitan Park System

Geo. H. Walker & Co.; League of American Wheelmen

1898

Boston Public Library

In the late nineteenth century, the development of Boston’s metropolitan park system was spurred on by two key forms of transportation infrastructure: the electric street railway and the bicycle. Bicycling boomed in popularity during this time, as modern, inexpensive bicycles entered mass production and became an easily accessible form of go-anywhere mobility. This 1898 map above, commissioned by the League of American Wheelmen, shows how parks throughout the urban region were connected together by bicycle routes, depicted as red lines. Bicyclists were some of the earliest advocates for surface road improvements, and bicycling also offered an exciting opportunity for women to get around the city on their own at a time when the feminist movement was paving the way for women to spend time independently in public spaces. Bicycle infrastructure was mostly removed from streets as automobiles took over in the twentieth century, but many advocates today see it as an inexpensive and climate-friendly option for getting around. Bicycling also extends the range of other forms of transit by making it possible to travel further and faster from stations.

UP4.2

“Boston Bike Network,” from Go Boston 2030 (p.153)

Boston Transportation Department

2017