Indigenous Routes

Four centuries ago, English colonists did not arrive at the head of Massachusetts Bay to lands devoid of existing settlement or transportation corridors. The Massachusett people and other tribes in the region utilized natural waterways in combination with ancient footpaths, known as “traces.” European settlers built upon existing networks of canoeable waters, portages between waterways, and countless miles of traces.

This 1639 map by William Wood was first published in 1634, 1.1A just four years after the Massachusetts Bay Company established Boston on the Shawmut peninsula. It depicts a network of natural waterways which were the earliest and most accessible travel routes for both Indigenous people and the English colonists who were trying to claim the territory for their own.

1.1A

The South Part of New England, as It Is Planted This Yeare, 1639

William Wood; John Dawson

1639

Mapping Boston Collection

Canoes, the earliest form of maritime transport in Massachusetts Bay, are pictured in an engraved view from 1848, 1.1B framed by the three peaks of “Trimountaine” on the Shawmut Peninsula.

1.1B

Boston Notions, Detail from from title page

Nathaniel Dearborn

1848

WardMaps LLC

Early Connections

Scores of decades elapsed before overland travel around Massachusetts Bay was as direct or expedient as water travel. Hence, the first example of public transportation in Boston came by sea.

Public transportation for Boston is as old as the city itself. Within months of establishing their settlement in Boston, the Massachusetts Bay Company sought to facilitate movement across the Charles River. The General Court of the company, at its first meeting in Boston on November 9, 1630, agreed to solicit for ferry service, and approved an initial fare of one pence per person. By summer 1631, the Charlestown Ferry, Boston’s first public transit line, was up and running under private management.

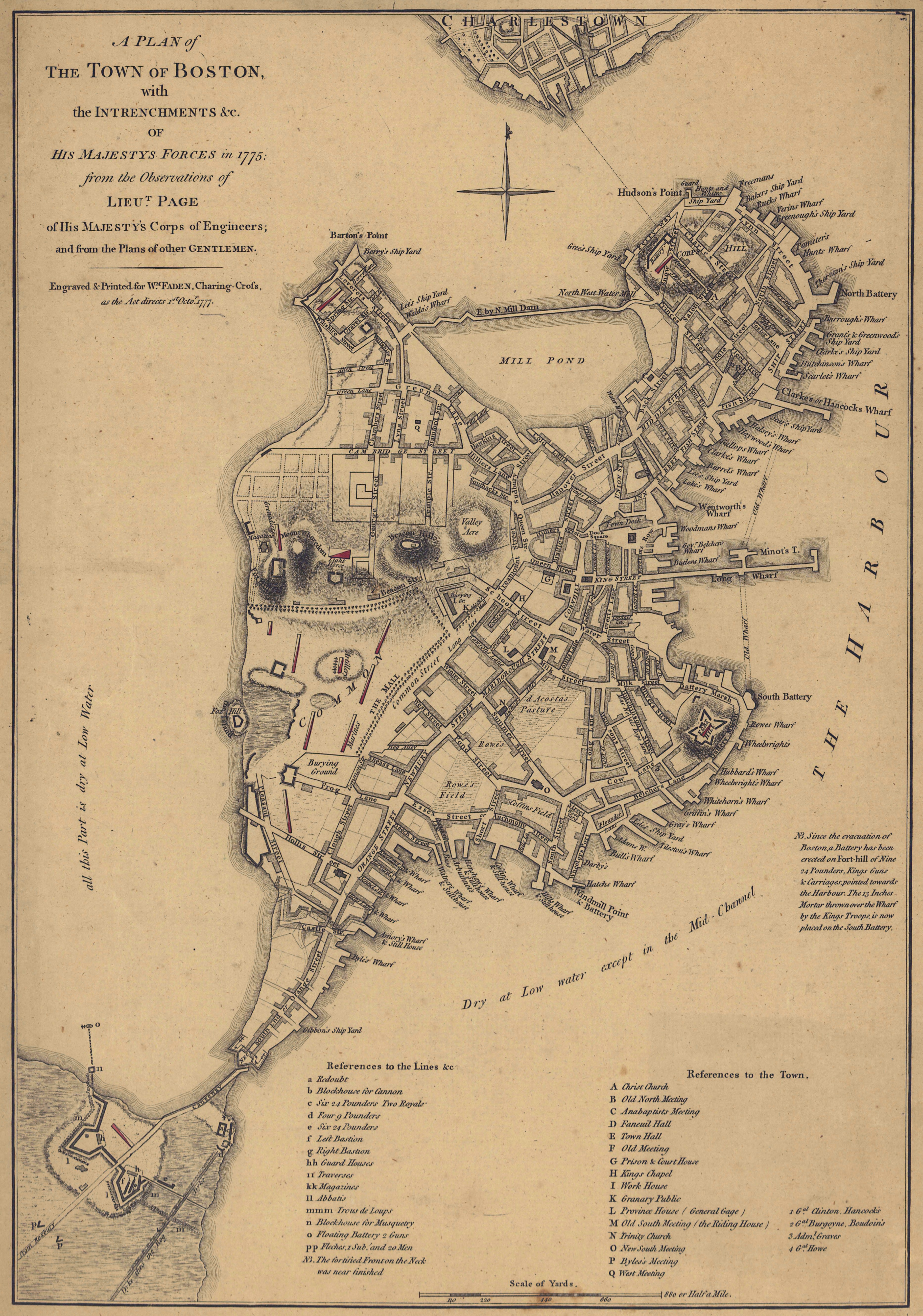

Nearly a century and a half later, a map made by a British military engineer 1.2A documented the vital ferry route, running between “Ferry Way” in the North End and Charlestown. By this point, Boston’s population had increased from less than 100 to around 16,000, making ferry travel increasingly crowded. As early as 1720, the General Court discussed replacing the Charlestown Ferry with a bridge across the Charles River.

1.2A

Detail from “A Plan of the Town of Boston With the Intrenchments &c. of His Majesty’s Forces in 1775”

Sir Thomas Hyde Page

1775

WardMaps LLC

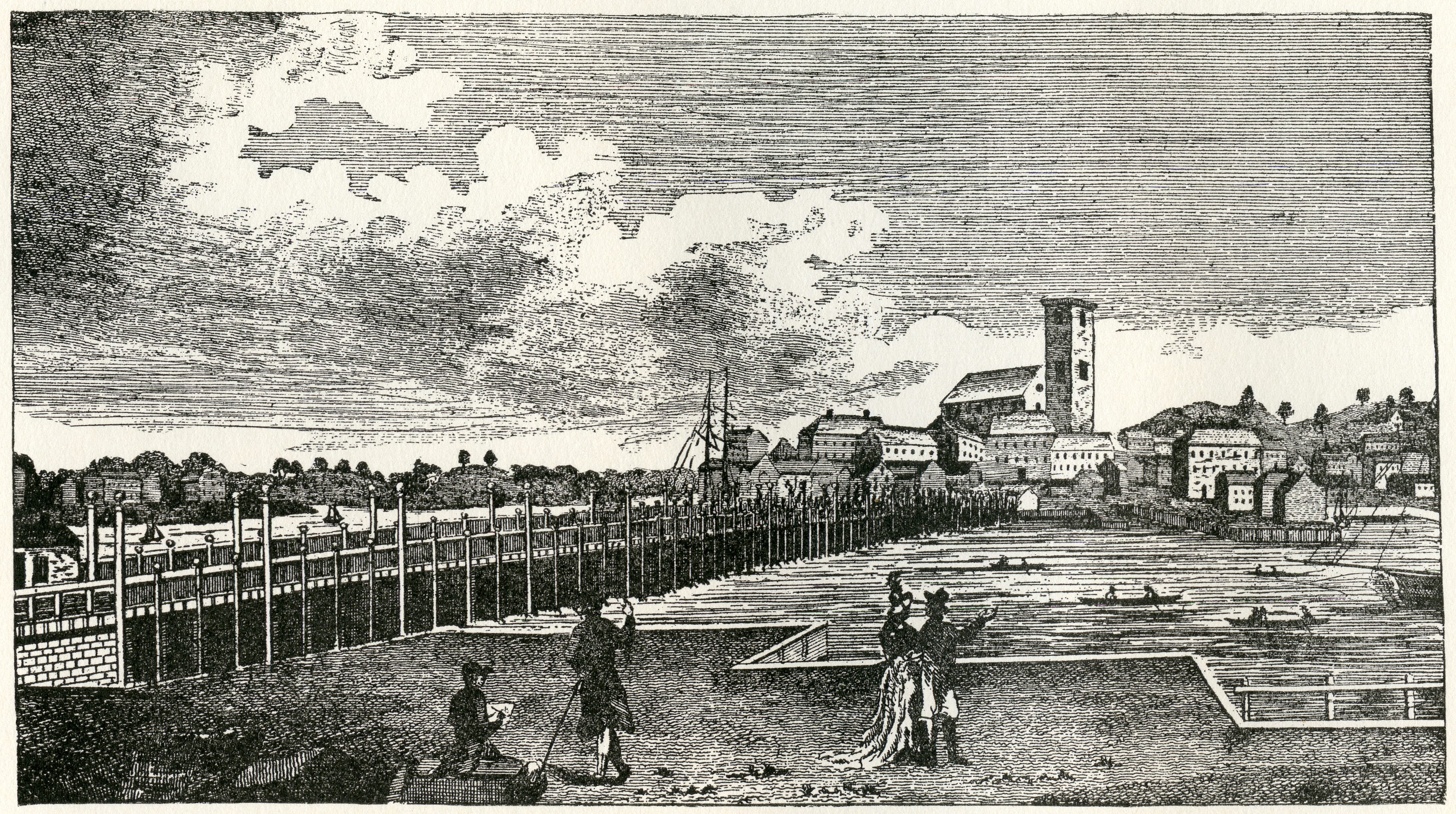

Opened in 1784, the Charles River Bridge was only the second fixed connection (after Boston Neck) between the Shawmut Peninsula and the mainland. A map made just after the American Revolution 1.2B shows the new bridge, labeled “Bridge erected 1786.” At the top of the map is the “Ferry to Winnisimet,” part of today’s Chelsea.

A view of the 42-foot wide Charles River Bridge, 1.2C complete with lanterns that illuminated its wooden deck at night, was published in Massachusetts Magazine in 1789.

1.2C

“Charles River Bridge” from “Antique Views of Ye Towne of Boston”

Morse-Purce Co.

1907 [1789]

WardMaps LLC

Coaches & Omnibuses

By the end of the first quarter of the eighteenth century, for-hire public coaches had become the backbone of overland public transportation in Boston and around Massachusetts Bay. A century later, in 1830, Boston’s population exceeded 60,000 for the first time. To accommodate the vastly increased demand for service, coach operators brought a new vehicle to the streets of Boston—the omnibus.

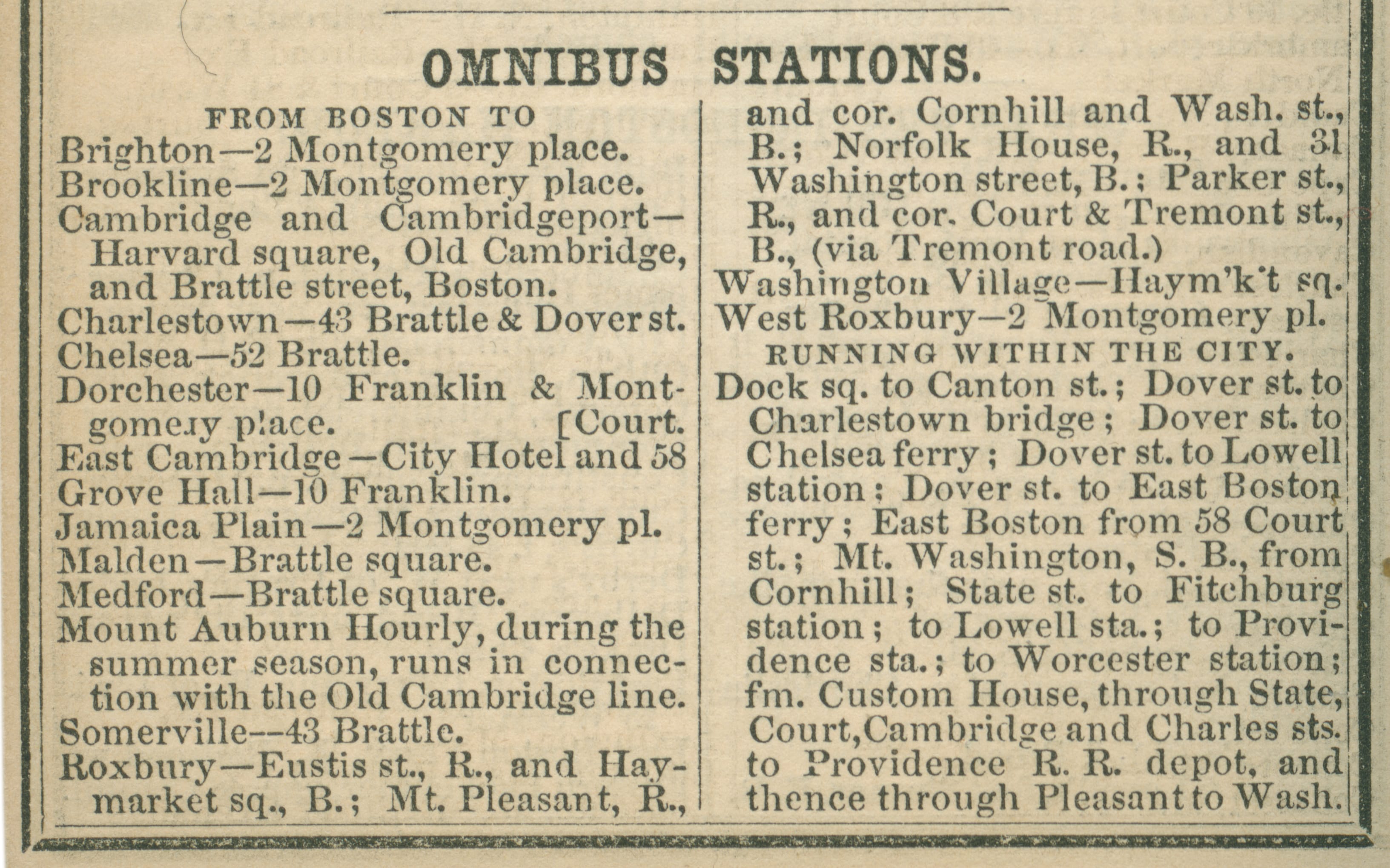

An 1850 listing of omnibus lines in the Boston Almanac 1.3A was among the first to simplify complicated origin and destination tables into a list of departure locations and routes. Around the same time, three core aspects of modern public transportation were developed with omnibus service: metal tokens for fare payment, center-aisle transit vehicles, and coordinated local and express service. Bus stops had arrived.

1.3A

“Omnibus Stations” from “The Boston Almanac for the Year 1850”

Coolidge & Wiley

1850

WardMaps LLC

An engraved view 1.3B shows Tremont Street in 1850s. Horse-drawn carriages, coaches, and omnibuses travel between Boston Common (far left) and Scollay Square (out of view far right). Omnibuses, distinguishable from coaches by their lack of side doors, are signed for Jamaica Plain and Brookline.

1.3B

Detail from “Grand Panoramic View of Tremont Street, Boston, East and West Sides From Court Street to the Common”

Frederick Gleason

1853

WardMaps LLC

Steam Railroads Proliferate

Railroad mania, an unprecedented, rapid construction of steam railroad lines associated with the early industrial revolution, came to Boston in the late 1820s and early 1830s.

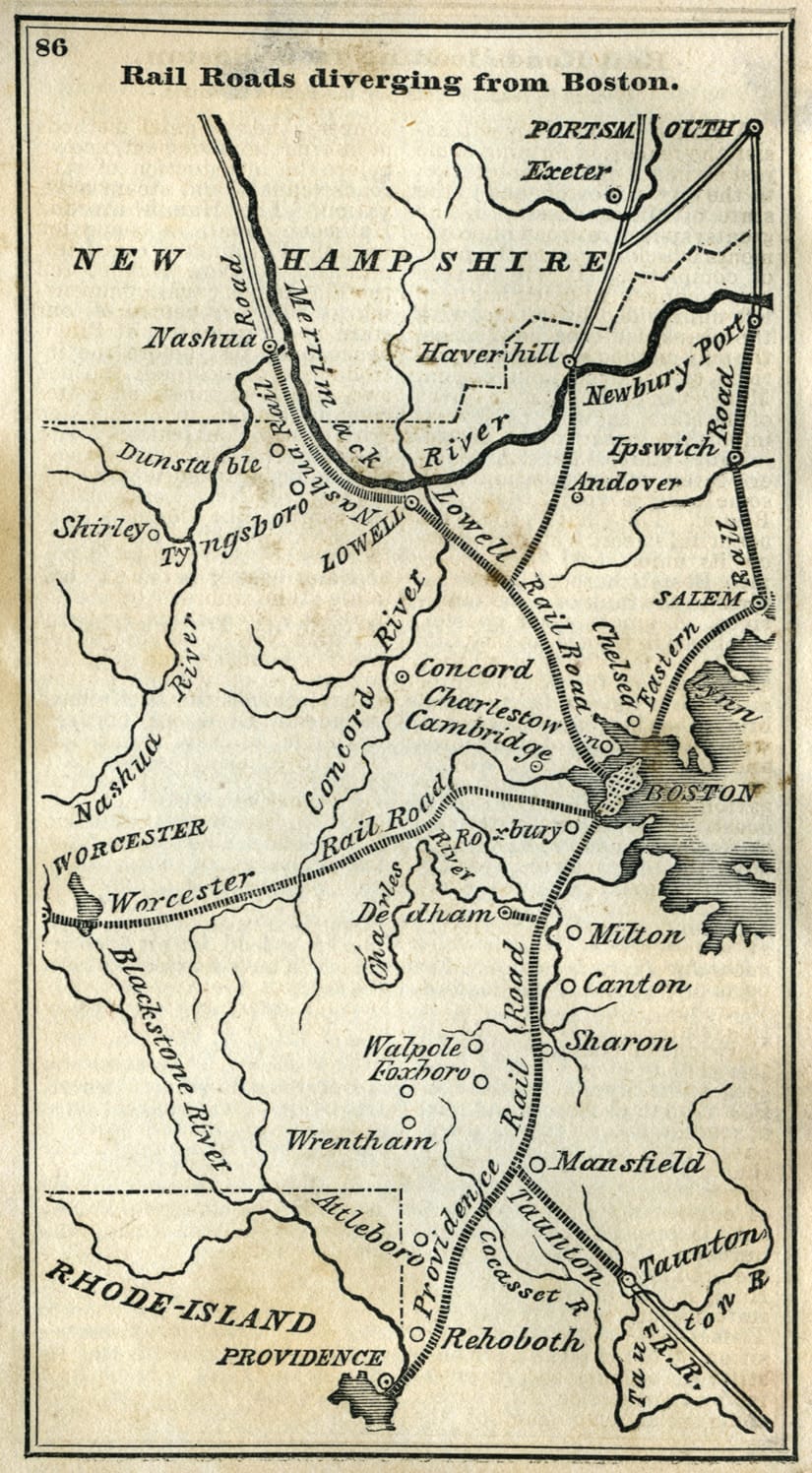

By 1840, this map from the The Boston Almanac 1.4B captured the main lines of the Eastern, Boston & Lowell, Boston & Worcester, and Boston & Providence Railroads radiating from Boston.

1.4B

“Railroads Diverging From Boston” from “The Boston Almanac”

S.N. Dickinson; Thomas Groom

1840

WardMaps LLC

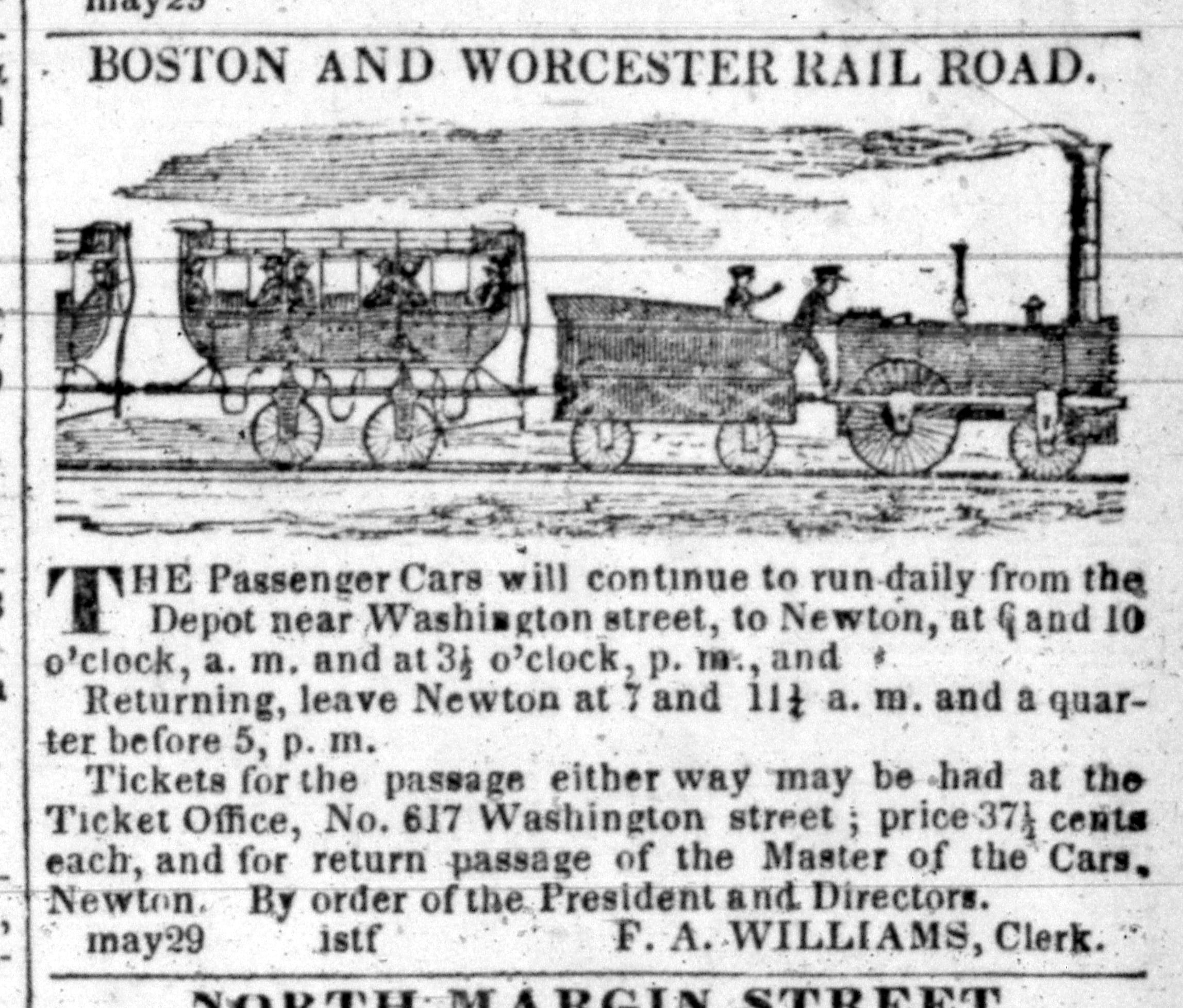

The Boston & Worcester was the first company to provide regular service to paying passengers in Boston, with trains running between downtown and West Newton in April 1834. An advertisement printed in an 1834 issue of the Boston Courier 1.4A depicts a train consisting of a primitive steam locomotive, a tender, and stagecoach-type passenger coaches.

1.4A

Boston & Worcester Railroad advertisement in May 29, 1834 issue of “Boston Courier”

1834

Boston Public Library

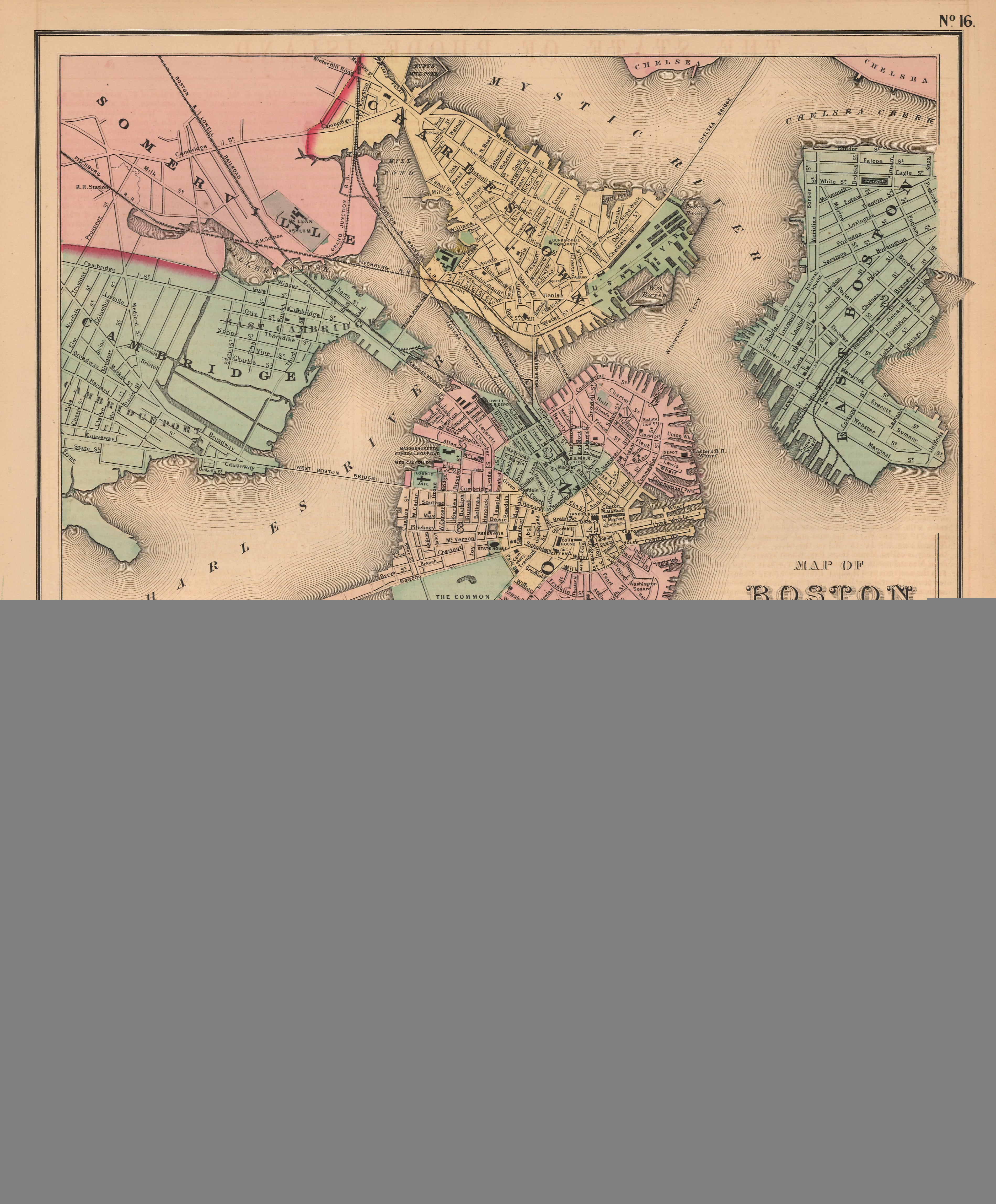

By the middle of the 1850s, eight different steam railroad companies provided passenger service to and from Boston. The lines of these eight companies became the foundation of today’s MBTA commuter rail network. Colton’s 1857 map of Boston 1.4D shows Boston connected to the mainland by numerous bridges and causeways, many of them supporting steam railroads. From the north, lines of the Boston & Lowell, Boston & Maine, and Fitchburg Railroads cross the Charles River into Boston and terminate around Causeway Street. From the west, lines of the Boston & Worcester and Boston & Providence Railroads cross the Back Bay onto the Shawmut Peninsula. From the south, lines of the Boston & New York Central and Old Colony Railroads cross South Bay and Fort Point Channel, respectively. From East Boston via Charlestown, the Eastern Railroad’s line reaches Causeway Street, between the lines of the Boston & Lowell and Boston & Maine.

1.4D

Map of Boston and Adjacent Cities

J.H. Colton & Co.

1857

WardMaps LLC

Each steam railroad company erected its own Boston passenger Terminal. The front page of an 1856 issue of Ballou’s Pictorial 1.4C depicts, clockwise from the bottom left, the early depots of the Boston & Maine, Eastern, Boston & Lowell, Old Colony, Boston & Providence, and Boston & Worcester Railroads. In the center is the Fitchburg Railroad’s “castle” depot.

1.4C

Front page of March 8, 1856 issue of “Ballou’s Pictorial”

1856

WardMaps LLC

Horsecars Ply The Streets

In the 1850s, responding to the unprecedented demand for local transportation and tapping recent developments in steam railroad conveyance technology, entrepreneurs brought a new mode of public transportation to the streets of Boston—the horse railroad.

An 1857 map of Cambridge 1.5A and an 1857 map of Boston, 1.5B published to accompany pocket-sized directories and almanacs, depict cities at the dawn of streetcar transportation.

1.5A

Map of the City of Cambridge, Mass.

W. A. Mason

1857

Leventhal Map & Education Center

1.5B

New Map of Boston, Comprising the Whole City, With the New Boundaries of the Wards

George W. Boynton

1857

Leventhal Map & Education Center

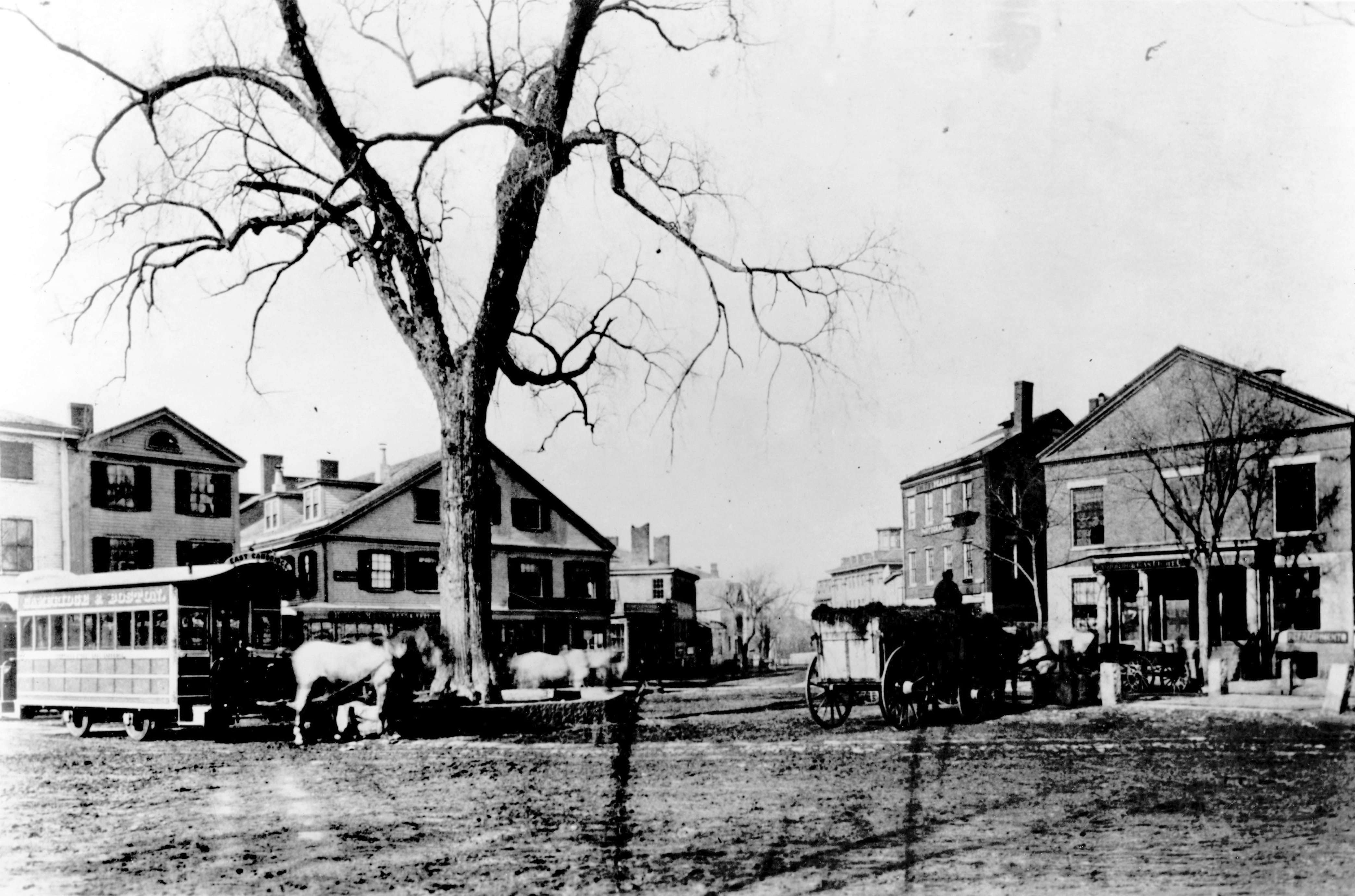

With five used horsecars purchased from the Brooklyn City Railroad, the Cambridge Railroad commenced Boston’s first public street railway service on March 26, 1856. A notation on the top left of this 1857 Cambridge map 1.5B reads “The dotted lines through Main St. Brattle St. and North Avenue, show the route of the Horse Rail Road.” An 1858 photograph 1.5C captures early Cambridge Railroad horsecars at Harvard Square.

By 1865, control of street railway operations had consolidated into four companies: the Metropolitan, South Boston, Middlesex, and Cambridge Railroads. An 1856 view 1.5D shows people running to catch a Metropolitan horsecar departing from upper Tremont Street.

1.5D

“The Metropolitan Horse Railroad, Tremont Street, Boston” from December 13, 1856 issue of “Ballou’s Pictorial”

1856

WardMaps LLC

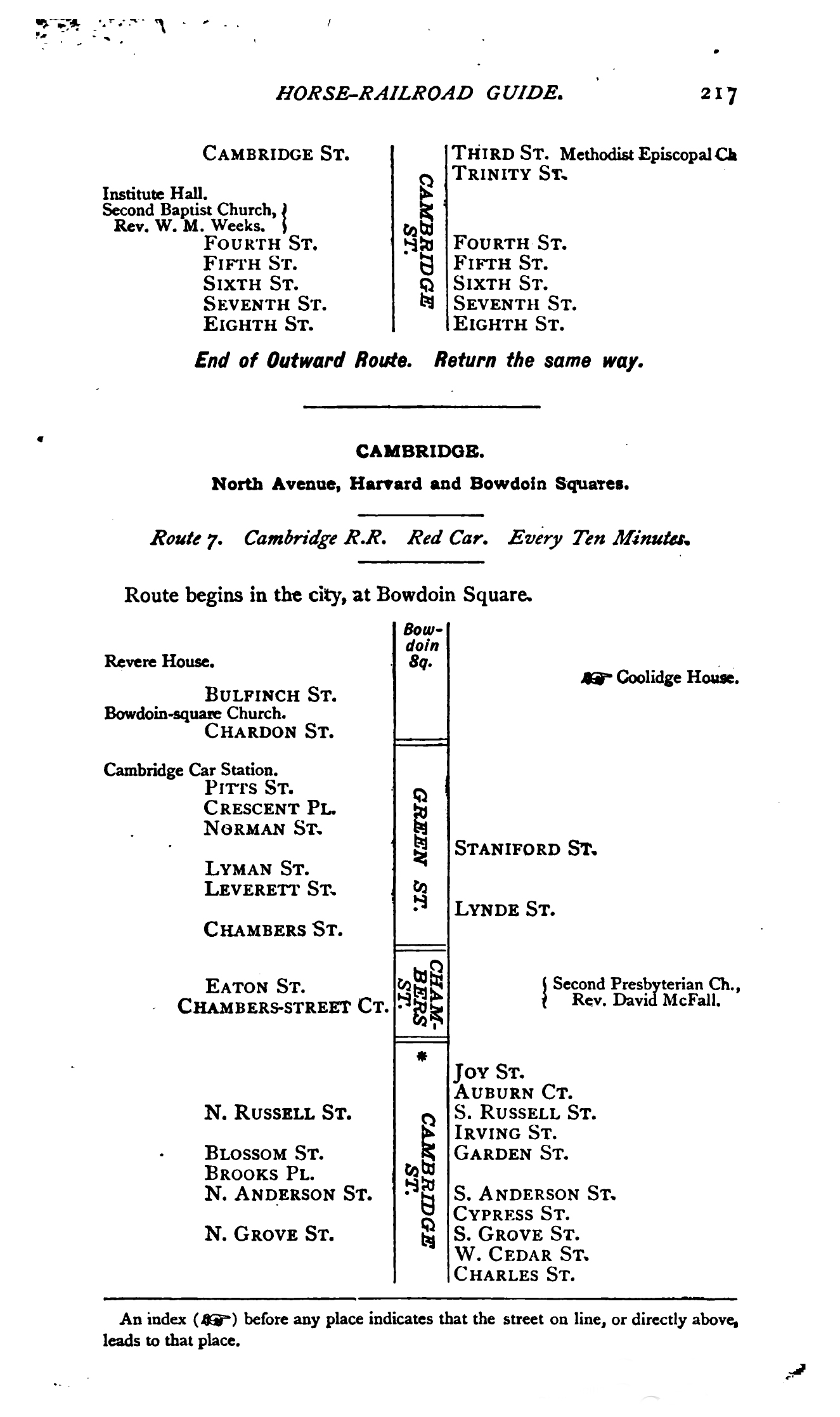

Three pages from the 1887 Boston Horse and Street Railroad Guide 1.5E describe Cambridge Railroad “Route 7” serving “North Avenue, Harvard and Bowdoin Squares.” The Route 7 diagram, along with others in the 1887 guide, was among the earliest examples of a local transit line map printed for the traveling public.

1.5E

“Cambridge Route 7” from “The Boston Horse and Street Railroad Guide”

Edward E. Clark

1887

Harvard University Libraries