Merchants Row was a site of trade, slavery, and political unrest in eighteenth-century Boston. The warehouses along this street, including those owned by Peter Faneuil, slave trader and namesake of Faneuil Hall, stood as physical reminders of the links between commerce and slavery. During the colonial period this was a key site of the slave trade, where humans were bought and sold. During the Revolution, some of the same buildings became landmarks of resistance, where merchants like John Hancock organized against political oppression. The geographic overlap echoes America’s foundational paradox: a revolutionary fight for liberty conducted amid the continued practice of human bondage.

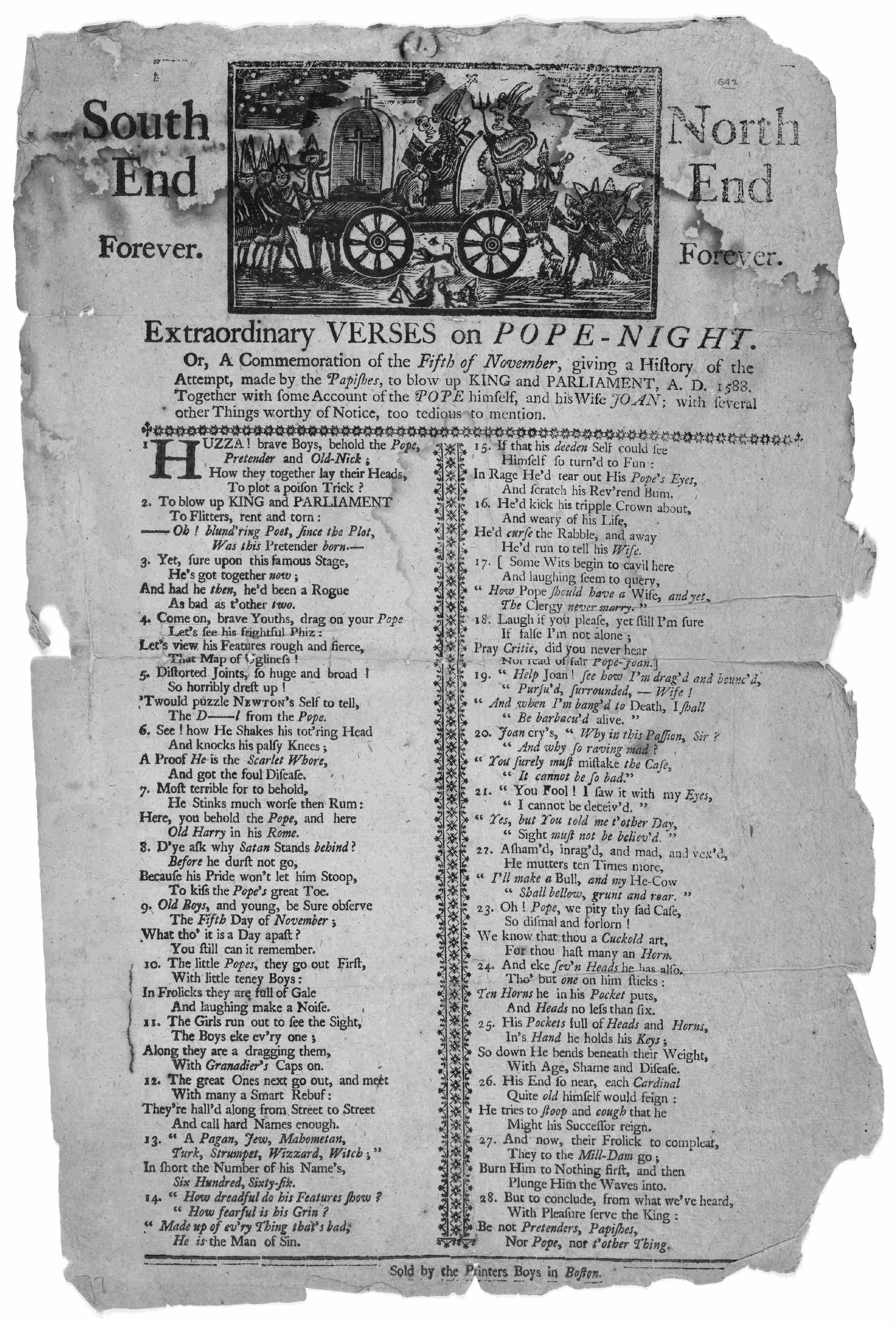

In the 1760s, Boston’s streets weren’t just pathways; they were landmarks of public protest. This broadside captured Pope Night celebrations as they morphed from traditional anti-Catholic observances into political protest during and after the Stamp Act crisis. The typical effigies of the Pope and Devil were joined by caricatures of unpopular British officials. References to rival North and South End neighborhoods, wagons, and celebrating crowds illustrate how colonial grievances found expression through public celebration.

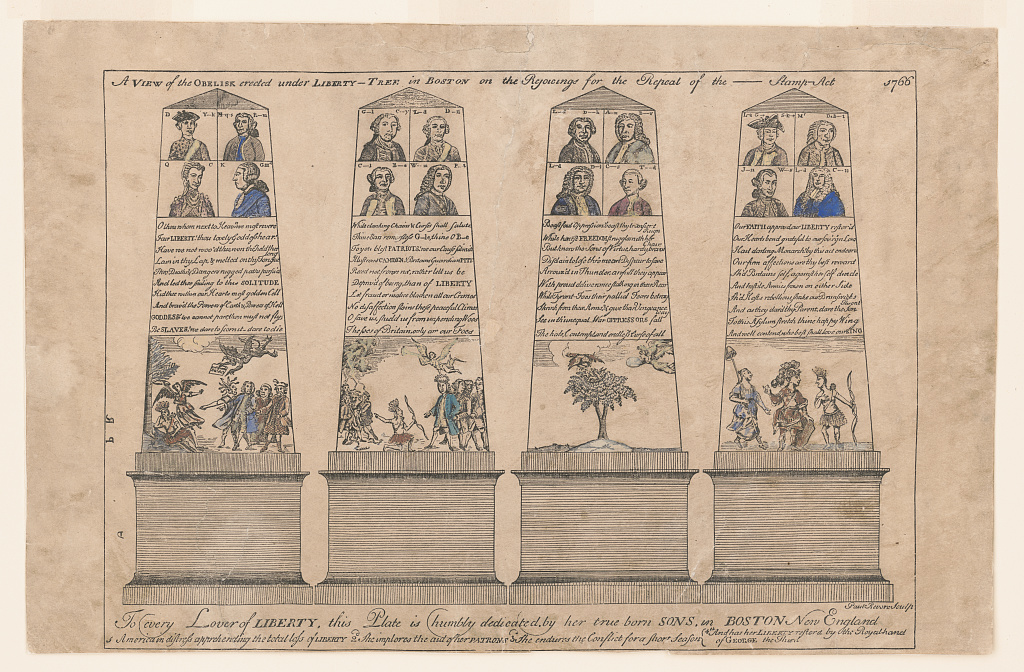

Paul Revere’s 1766 engraving depicts a four-sided obelisk, or monument, erected near Boston Common to celebrate Parliament’s repeal of the Stamp Act. The obelisk, which stood for just a short time, features imagery honoring British leaders and proclaiming loyalty to King George III, while celebrating the colonists’ restored rights and liberties. Physical monuments like this obelisk served as public message boards in an era before electronic communication. They provided spaces where colonists gathered to develop their shared identity and political awareness.

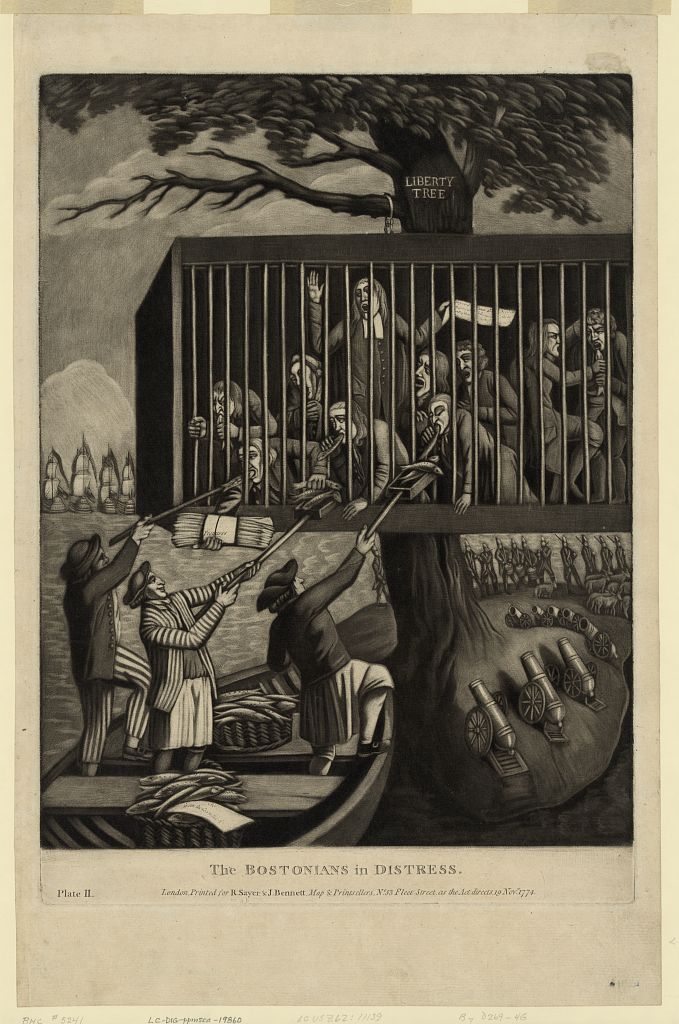

Even the natural landscape could serve as a landmark. Liberty Trees were used by both Patriots and Loyalists as powerful symbols of colonial resistance, either to mobilize or mock. One tree grew at the intersection of Washington and Essex Streets in downtown Boston. Today it is marked by a colorful plaque. This print, produced following the Boston Tea Party and the closing of the Boston Harbor under the Coercive Acts, was circulated widely in British newspapers. It pokes fun at Bostonians’ claims for liberty, depicting them imprisoned in a cage suspended from a Liberty Tree. Three British sailors feed the prisoners fish in exchange for a packet of papers.

Boston’s Quaker Lane, once notable for its meeting house, became a landmark of peaceful resistance during the Revolution. Upholding their commitment to non-violence, Quakers joined ordinary men and women outside the political elite in turning to boycotts and non-importation to express discontent with British rule. As leaders of the Homespun movement, Quakers encouraged colonists to make their own clothing instead of buying British goods. The movement included many women who organized community spinning bees and managed their families’ purchases of textiles and clothing.

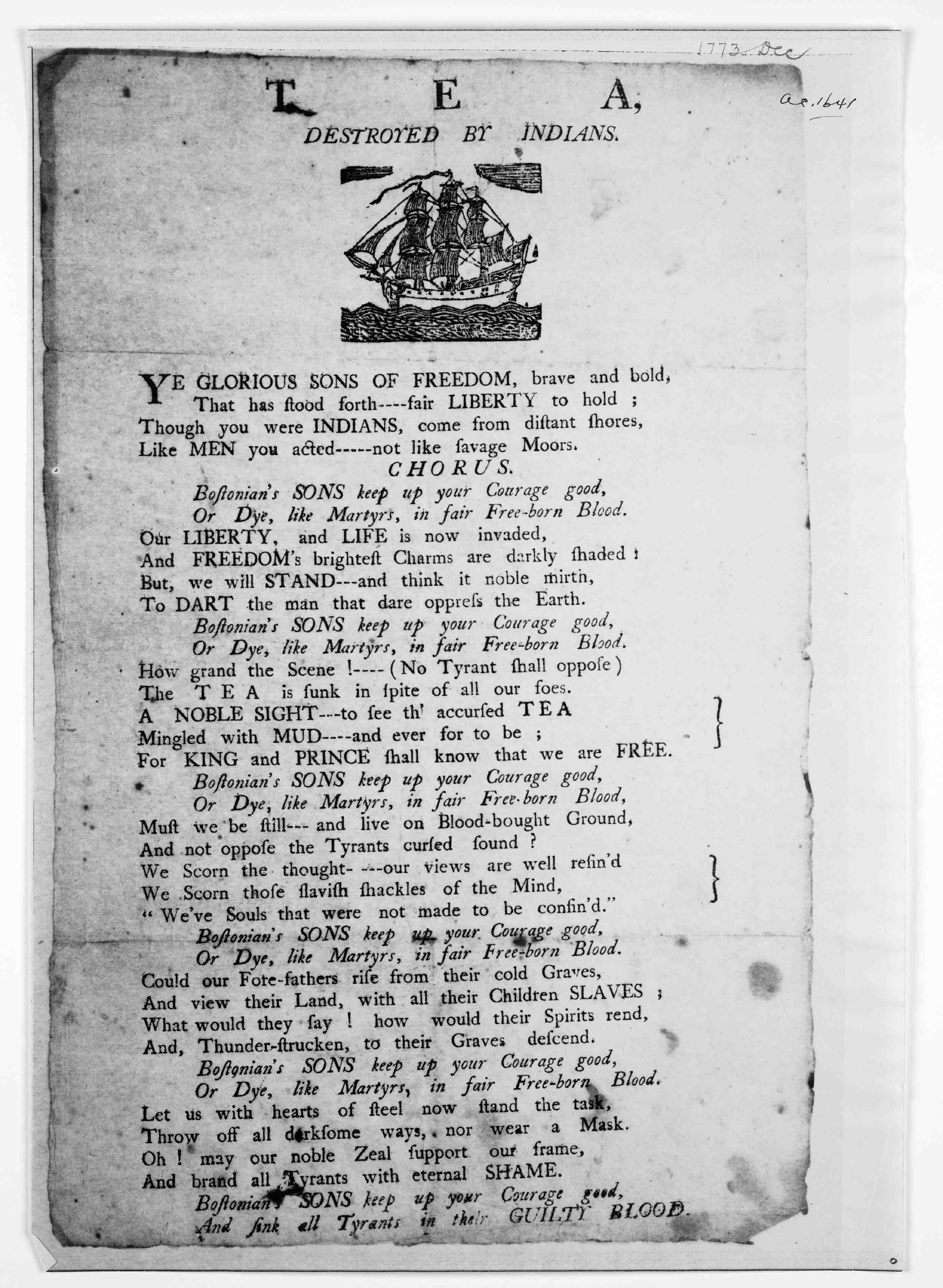

Revolutionary landmarks were referenced in all forms of popular culture, including widely published broadsides. This poem commemorates the Boston Tea Party of December 16, 1773, when colonists, disguised as Indigenous people, ventured to Griffin’s Wharf and dumped 342 chests of British tea into the harbor to protest taxation policies. The title’s reference to “TEA, DESTROYED BY INDIANS" both acknowledges the colonists’ disguise and celebrates their act of rebellion. Using powerful maritime imagery with the ship woodcut at the top, the poem frames the Tea Party as a gallant stand for liberty, capturing a moment when Boston’s resistance to British rule was openly celebrated.

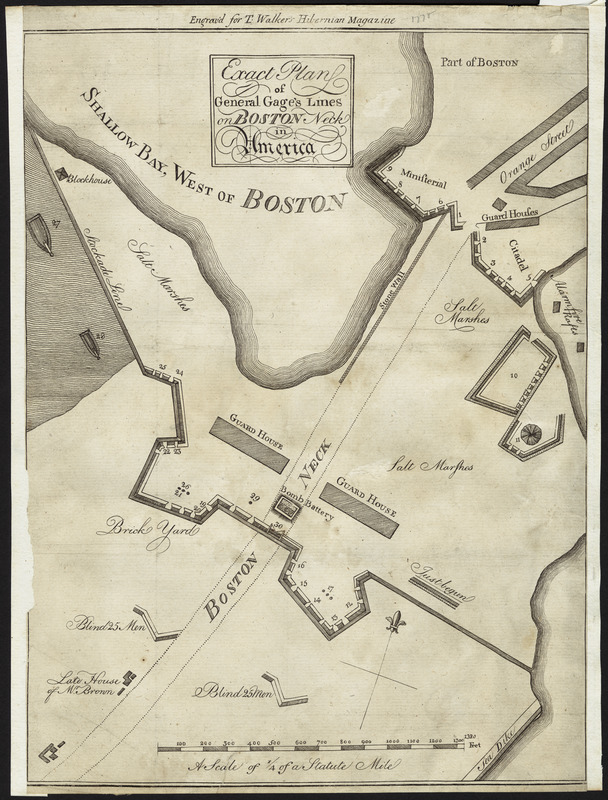

During the siege of Boston from 1775 to 1776, British forces blockaded the Neck, the narrow strip of land that connected the city to the mainland. These fortifications protected British troops from colonial forces, while punishing New Englanders by cutting off the only land route into Boston. This widely printed image made Boston Neck a recognizable landmark for colonists elsewhere, introducing readers to detailed intelligence about British military defenses in Boston.

Boston’s Revolutionary landmarks span geography and generations. In this photo, an unnamed Black man stands beside the Prince Hall Monument in Copp’s Hill Burying Ground, an 1895 memorial marking the burial site of Prince Hall. Hall was a freed Black man whose life intersected with key Revolutionary sites across Boston Harbor. At Castle William, a strategic British fortification shown in the plan on the next page, Hall and fourteen other free Black men made history in 1775 when they were initiated into Freemasonry through a British military lodge. While the British would later burn Castle William during their retreat from Boston in March 1776, Hall’s legacy endured through his activism and leadership. Today, his gravesite has become a landmark and destination for Freemasons and civil rights advocates from around the world. It stands in stark contrast to the thousands of unmarked graves of Black Bostonians from the seventeenth through nineteenth centuries buried nearby.