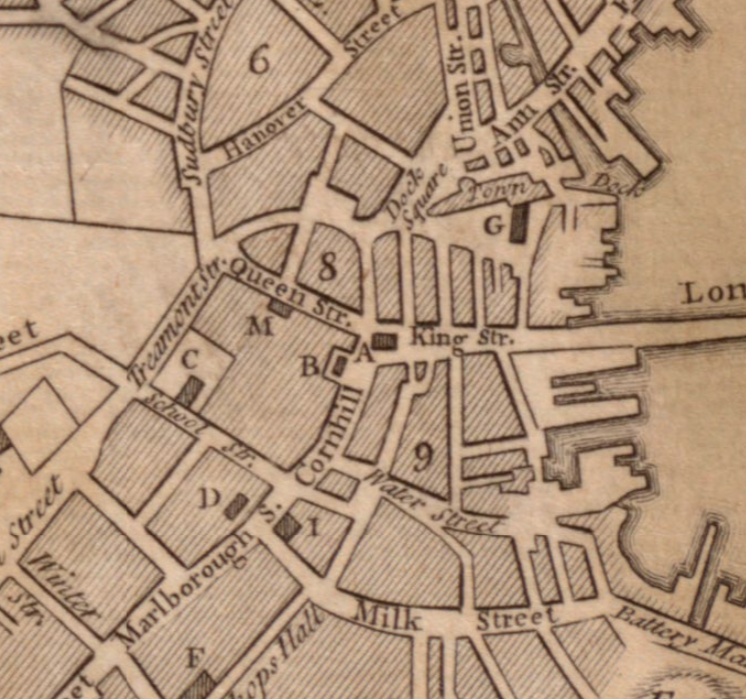

This map tells us a lot about the outbreak of violence that shaped life across New England in 1775. It includes several key battles and troop movements in Massachusetts, including Lexington and Concord in April, Bunker Hill and Charlestown in June, and General George Washington’s arrival to command the colonial forces around Boston in July. During this three-month period, word of military clashes between rebels and British troops spread. This map, printed in London, helped inform the public about the war unfolding in the distant American colonies. It quickly became a crucial source of geographic information about the war; even Washington himself kept a copy in his personal collection.

Behind the notes of troop movements and battles on this map lie the individual stories of people who found themselves entangled in war. About 20,000 militiamen ventured to Massachusetts to support the Continental Army. While George Washington is named, most soldiers represented are anonymous. Their ranks included not only white colonists, but also Black and Indigenous men who joined the revolutionary cause despite being denied basic rights and citizenship—the very freedoms they helped secure for others through enlistment.

The Bridge 19th of April

Luther Jotham (c. 1751–1832), a free Black man, joined the Bridgewater Minute Men and fought at Lexington and Concord. His service offered steady pay, a pension, and a chance at social equality. He served in the Continental Army under Colonel Cary during the British evacuation of Dorchester Heights, and enlisted for four terms, ending in October 1777.

March of the New Hampshire Troops

Jude Hall (c. 1760–1827), a formerly enslaved man from New Hampshire, joined the Third New Hampshire Regiment and fought at Bunker Hill. Hall was reportedly thrown off his feet by a cannonball blast but survived to fight at Ticonderoga, Trenton, and Saratoga. Despite eight years of service, Hall’s life was marred by the Revolution’s unfulfilled promise of liberty. His sons, though born free, were later kidnapped and sold into slavery in Louisiana and the West Indies. He never saw them again.

Bunker’s Hill

At Bunker Hill, at least 15 Indigenous soldiers fought for the Continental Army, representing the Mashpee Wampanoag, Hassanamisco Nipmuc, Tunxis, Mohegan, and Pequot tribes. Eight served in Captain John Durkee’s integrated company. Their reasons for enlisting were complex. Some shared white colonists’ frustrations with British taxation; others saw military service as a way to maintain local alliances with their white neighbors. The Stockbridge-Munsee Mohicans were the first Indigenous group to enlist, possibly influenced by their conversion to Protestantism.

English Forces

While no Black Loyalists fought for the British at Bunker Hill, an estimated 80,000-100,000 enslaved people escaped to British protection following Lord Dunmore’s 1775 proclamation offering freedom to those who joined the British side. The “Book of Negroes,” from the 1783 British evacuation of New York, records 18 people from Massachusetts, including the Slade family—Freelove, her husband Lot, and their son Roger—who escaped in 1779. They helped establish Birchtown, Nova Scotia, and later a free Black community in Sierra Leone.

March of General Washington

George Washington, Commander in Chief of the Continental Army, initially opposed Black and Indigenous enlistment. When the British offered freedom to enslaved people who joined their ranks, he changed his mind. By 1776, he allowed already-serving free Black soldiers to remain. Between 5,000 to 8,000 Black soldiers served with the Continental Army.

Town Hall

In Massachusetts, enslaved people fought for their freedom through legal means, often appealing to principles that derived from New England’s experiments with democratic government. Black women often led this charge. In 1773, a group of enslaved residents petitioned the Massachusetts General Court, questioning how colonists could demand liberty while denying it to others. Elizabeth Freeman (c. 1744–1829), born “Mum Bett,” used the new state constitution, which declared “all men are born free and equal,” to successfully challenge slavery in court in 1781. Her victory set a powerful precedent, and Massachusetts later became first state to effectively abolish slavery in 1783.