Designed as an accessory that could be installed in any car, the Etak Navigator displayed in this case is the first “electronic road map.” Unlike our modern map apps, however, it operated without the aid of GPS. Instead, Etak combined “augmented dead reckoning” and “map matching” to update, in real time, a user’s location on a digital map.

Dead reckoning is the process of determining one’s current location based on a previous position and estimated speed, direction, and elapsed time. The Etak Navigator’s dead reckoning system depended on a compass and wheel sensors that detected strips of magnetic tape adhered to the inside of two of the car’s wheels. These sensors counted rotations of the tires, computing a new position from the previous one every second and matching these new coordinates to a digital street network. As the vehicle moved, the map would shift and rotate beneath an arrow symbol, maintaining the vehicle’s bearing and position along the way. This cartographic convention—an unmoving arrow in the center of a moving map display—is so ubiquitous now that we barely notice it, but it began with Etak. The Etak Navigator took its name from the Micronesian word etak, which describes a form of oceangoing dead reckoning that combined sea currents and constellations.

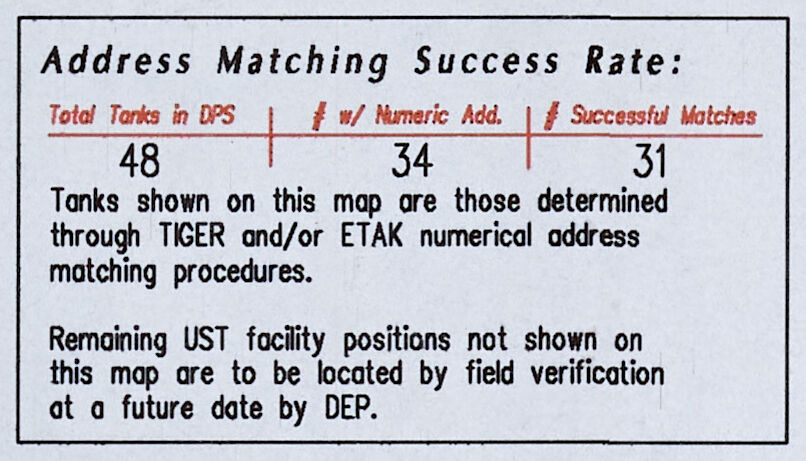

The Etak’s digital map files were stored on magnetic tape cassettes and displayed as vector data on a small screen by way of a cathode ray tube graphics processor. Three cassettes would cover the area greater San Francisco-Oakland-San Jose area. Outside of navigation, some digital mapping professionals also used the Etak software for the address matching process described in the section on Analyzing Nature."