A webwork of imaginary lines is all it takes to convert a set of stars that have nothing to do with one another into something recognizable: a dipper, a plow, a swan, an ancient hero. By stitching the points of light in the night sky together into constellations, human culture inserts the loom of interpretation between the universe and our understanding of it. Constellations thus offer a particularly useful starting point for thinking about the troublesome relationship between what actually exists in the world and the cultural systems that intermediate our knowledge of that existence. Are constellations real or imaginary, natural or artificial, out in the world or just in our heads?

Of course, they are clearly a bit of both: there aren’t really dippers, or plows, or swans, or ancient heroes in the sky. But those designs aren’t sketched on a blank canvas. The location and arrangement of the stars is actually real, and, at least on the scale of human lifetimes, immutable. What is more, we don’t each make up the constellations from our own individual imaginations alone; they’re handed down through shared cultures, such that we can speak meaningfully with someone who shares our reference system about the Big Dipper as if it really were a thing out in the world and not just a made-up figure in our heads.

A star constellation obviously confounds this distinction between what is known and what is “real,” but the same confusion is also at play in the terrestrial world. We may speak meaningfully about such geographic objects as cities, regions, prefectures, or empires as if the fact of their existence inheres in the shape of the world itself. But upon closer examination, these also turn out to hover somewhere between imagination and reality. There’s only a United States of America or a Guangdong province or any other geographic unit insofar as we collectively agree to recognize such objects—much like dippers and plows in the sky.

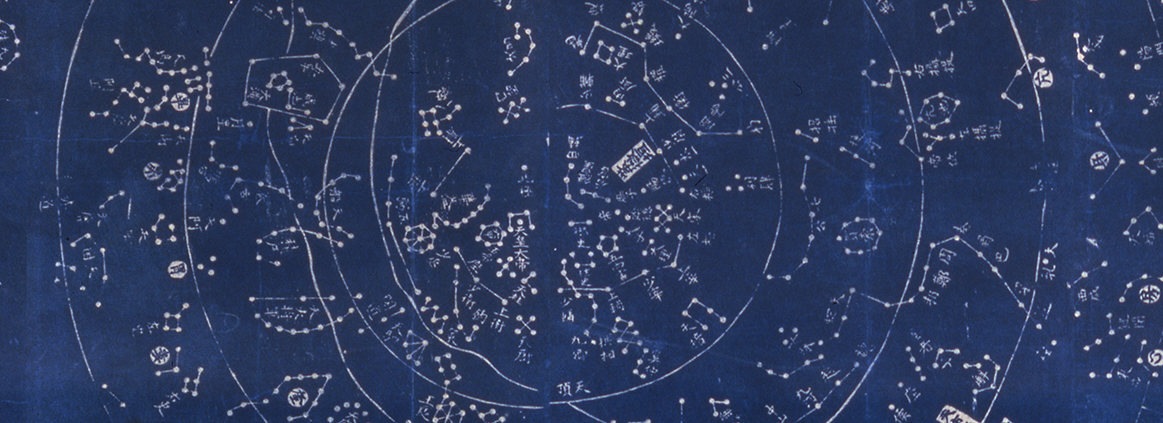

Unlike star constellations, these terrestrial formations play an instrumental role in politics and power, which is why rulers and administrators have always been so keen to map them and to fix them into place through mechanisms ranging from taxation to census tabulation. In Heaven & Earth, we see this double process of bringing cartographic order to the terrestrial and celestial worlds as it played out in Qing China. In the Chinese cosmographic tradition, heaven and earth were intimately related to one another. The patterns sketched out from the arrangement of the night sky offered practical guidance for how to conceptualize the world on the ground—and also how to govern it. When bureaucrats and functionaries aggregated statistical and administrative information from across the domain of the “unified all under heaven” Qing territory, and condensed the information into the figures and symbols of the terrestrial maps on display in Heaven & Earth, they were engaging in a form of knowledge systematization that was more than just circumstantially related to the work of astronomers and cosmographers who traced lines in the skies.

The formal connection between the celestial and terrestrial maps on display in Heaven & Earth—their twin derivation from stone stele rubbings and their unique use of the Prussian blue colorant—offers a prompt to think about how cultures come to make sense of both celestial and terrestrial space by gathering, structuring, and representing knowledge. Whether in dippers in the sky or districts on the ground, plows or provinces, the work of cartographers etches our imaginary systems of order onto the world.