Since the Western Han Dynasty (206 BCE–9 CE) in China, data sets of administrative information related to civil and military affairs were collected, collated, and then made manifest in tu. The Chinese term 圖 tu can translate into a number of different meanings like diagram, picture, map, painting, and so forth, all related to rendering three-dimensional space onto a two-dimensional plane. Historically, local administrators, both civil and military, were required to compile data sets and produce these tu. The tu considered here are those most associated with cartography, as they functioned as management tools for taxation, resource allocation, agricultural planning, travel, military strategy, and as symbols of ownership and authority. They often provided information like population densities, geophysical characteristics of place, types of buildings (religious, civil, military), local resources, and so forth.

These tu typically lack a uniform or specific style of appearance but were designed for instrumental purposes. In other words, makers were less concerned with what the tu looked like and focused on what they did and how they functioned. For example, the tu often do not have a uniform scale. Instead, toponyms or other data are presented positionally or relationally between points of reference (their positions relative to each other) and are “encoded.” These administrative cartographic materials became a distinctive Chinese typology that continued through the millennia.

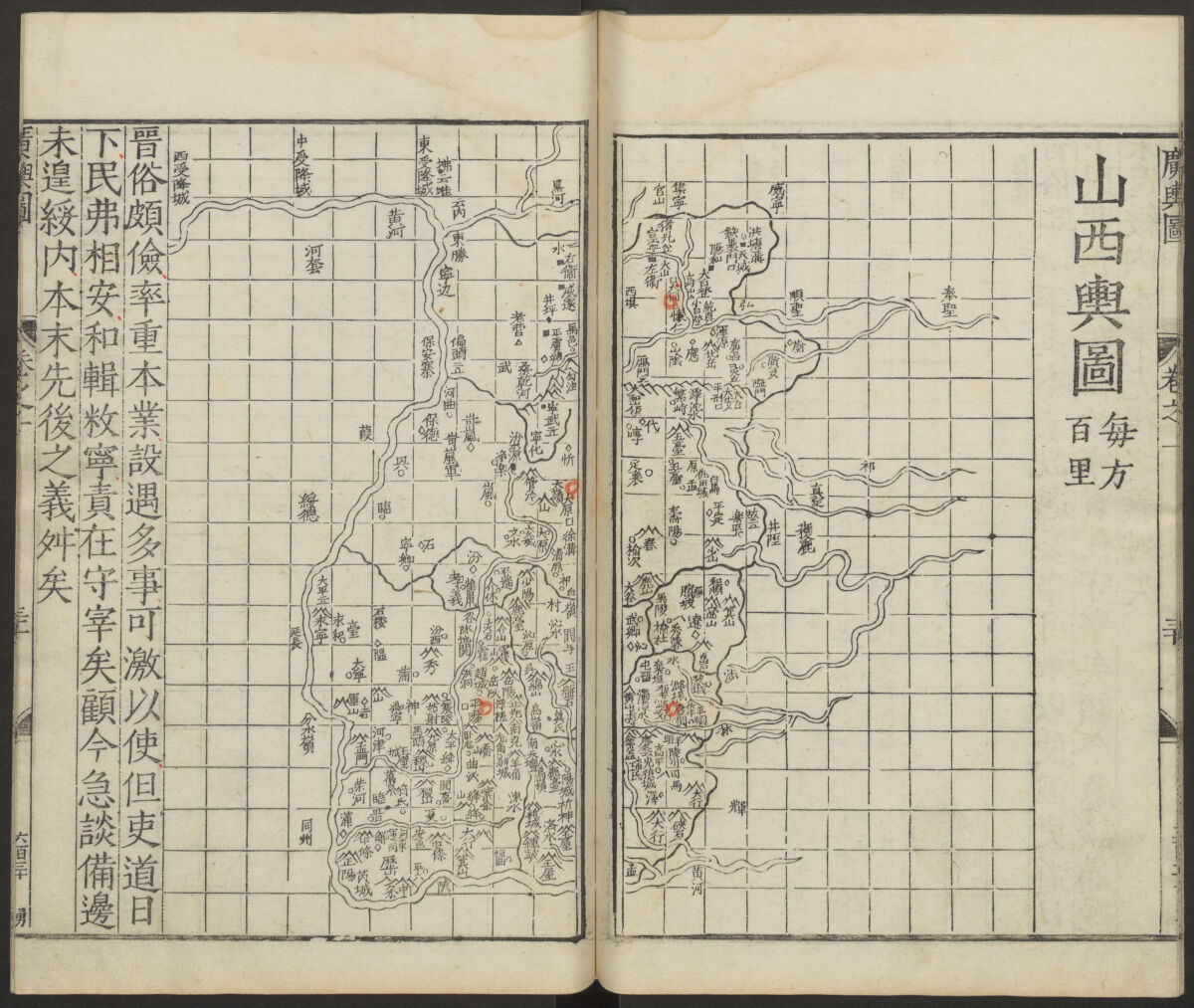

In the mid-sixteenth century, during the Ming dynasty (1368-1644), the first Chinese atlas, entitled Enlarged Territorial Atlas (廣與圖 Guangyu tu), was created by 羅洪先 Luo Hongxian (1504–64). Luo opens with a map of the Ming empire entitled Complete Terrestrial Map (輿地總圖 Yudi zongtu).

Maps of the eighteen provinces of the late Ming dynasty followed like this Map of Shanxi Province (山西輿圖 Shanxi yutu). If we look closely at a detail of that map we can see that many of the toponyms listed have small geometric shapes next to them, i.e. diamonds, circles, squares, and so on.

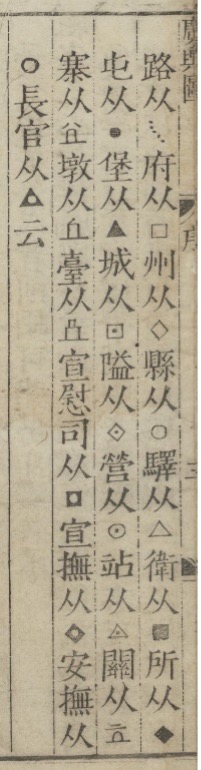

Luo compiled census figures, military information and tributary reports to create administrative data sets (listed in descending order of scale and bureaucratic importance) that are presented in a key found in the introduction of the atlas. The very broad range of civil, military and administrative bodies as well as distinctive geophysical characteristics associated with toponyms provides quite detailed information about the administrative and transportation operations of the province.

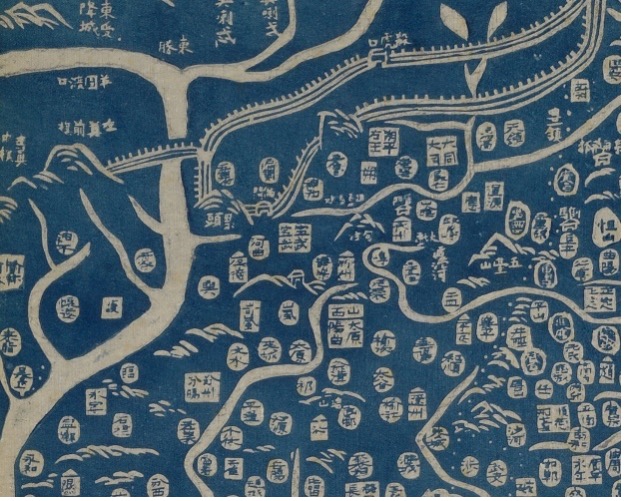

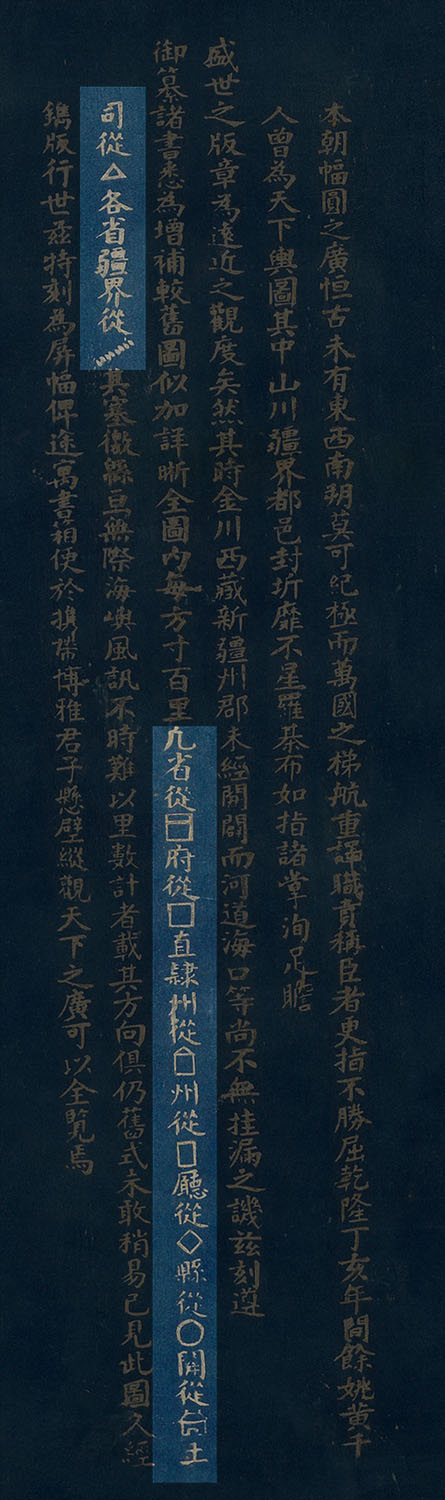

250 years later in the early nineteenth century of the Qing dynasty (1644–1910) a unique Prussian blue terrestrial map was created entitled Complete Geographical Map of the Everlasting Unified Qing Empire (大清萬年一統地理全圖 Daqing wannian yitong dili quantu).

Using the same detail of Shanxi Province we see here that administrative information is conveyed visually as well except that instead of a geometric shape alongside the toponym, each toponym is imbedded in a different geometric shape. The blue terrestrial map presents a key of nine symbols in the introductory text block found in the lower right corner of the map.

During the Qing dynasty the eighteen provinces (sheng) were divided into circuits (dao). The circuits were divided into prefectures (fu), independent departments (zhilizhou), and independent subprefectures (zhiliting). The prefectures were divided into counties (xian), departments (zhou), and subprefectures (ting). Thus, the blue terrestrial map provides a very accurate and detailed breakdown of the administrative structure for the entire empire in a single image.

A few of the geometric symbols on the blue Qing map are the same shapes as those found in the Luo’s earlier Ming dynasty atlas key. The difference being Luo placed the symbols by the toponyms and the blue map imbeds the toponym in the shape. These encoded toponyms, although using different visual presentations, conceptually function in the same manner. The use of geometric shapes in association with toponyms and administration is a characteristic of a typology of Chinese mapmaking that visually links places with the people of those places. This encoding visually prioritizes administration over territory, the people living in each administrative unit become more important than depicting information according to scale or geometry, as does the relational spacing of each toponym with the surrounding ones in an administrative hierarchy of the entire empire.

This manner of encoding toponyms is unique to Chinese administrative maps. They reflect the human system (administrative bodies like prefectures, sub-prefectures, counties, and so forth) of all places in the empire conceptually operating within a Chinese familial framework. If we consider these encoded toponyms as presenting a specifically Chinese paradigm of a socio-political order that has a familial framework, then the entire atlas and terrestrial blue map can be understood as presenting the paradigm of an idealized order that is the Ming or Qing empire. Within a specifically Chinese context this type of socio-political order with a familial framework was first proposed and implemented by Confucius (551–479 BCE) and his followers as a method to promote peace and stability on micro and macro scales. That is not to say that these maps are explicitly Confucian in any way but that they present similar paradigms. Confucianism, in its original formulation, before it was assimilated with other religious and ritual practices, is understood to be structured, on the micro-scale, as relationships between individuals within a family then applied, on the macro-scale, to relationships between individuals and humanity and then scaled up to groups and the larger world. A set of principles—including benevolence (ren 仁), righteousness (yi 義), propriety (li 禮), wisdom (zhi 智), sincerity (xin 信) and others—were created to maintain harmony and stability on the micro and macro scales. Each toponym is encoded through a shape that ties it immediately to the administration and a social structure.

The types of maps presented here visualize relationships within a Chinese administrative order found between the toponyms, geography, social structures, and the people that inhabit those spaces. The micro-scale familial relationships and social structure essential in understanding the macro-scale frameworks of the Ming and Qing realm and its mapping are valued and these maps precisely present the hierarchy visually.

Further Reading

Fuchs, Walter 1946. The "Mongol Atlas" of China by Chu Ssu-pen and the Kuang-yü-t'u : with 48 facsimile maps dating from about 1555, Fu Jen University, Peiping (Beijing).

Pegg, Richard A., 2024. Heaven and Earth: The Blue Maps of China, exh cat., Leventhal Map and Education Center, Boston Public Library.

Pegg, Richard A., 2024. “The Blue Terrestrial Map of China in the WereldMuseum, Leiden.” Provenance, WereldMuseum, Leiden, no. 5.

Pegg, Richard A. and Papelitzky, Elke, 2024. “The Blue Maps of China: Considerations of Materiality and Function in China and Japan,” in Maps and Colours, Federal Ministry of Education and Research, Germany, Brill, ch. 14, pp. 190-204.

Pegg, Richard A. and Papelitzky, Elke, forthcoming. The Chinese Blue Maps: Correlating Heaven and Earth in the Early 19th Century, MacLean Collection and University of Chicago Press.

Wang, Michelle 2023. The Art of Terrestrial Diagrams in Early China. University of Chicago Press.