About this object

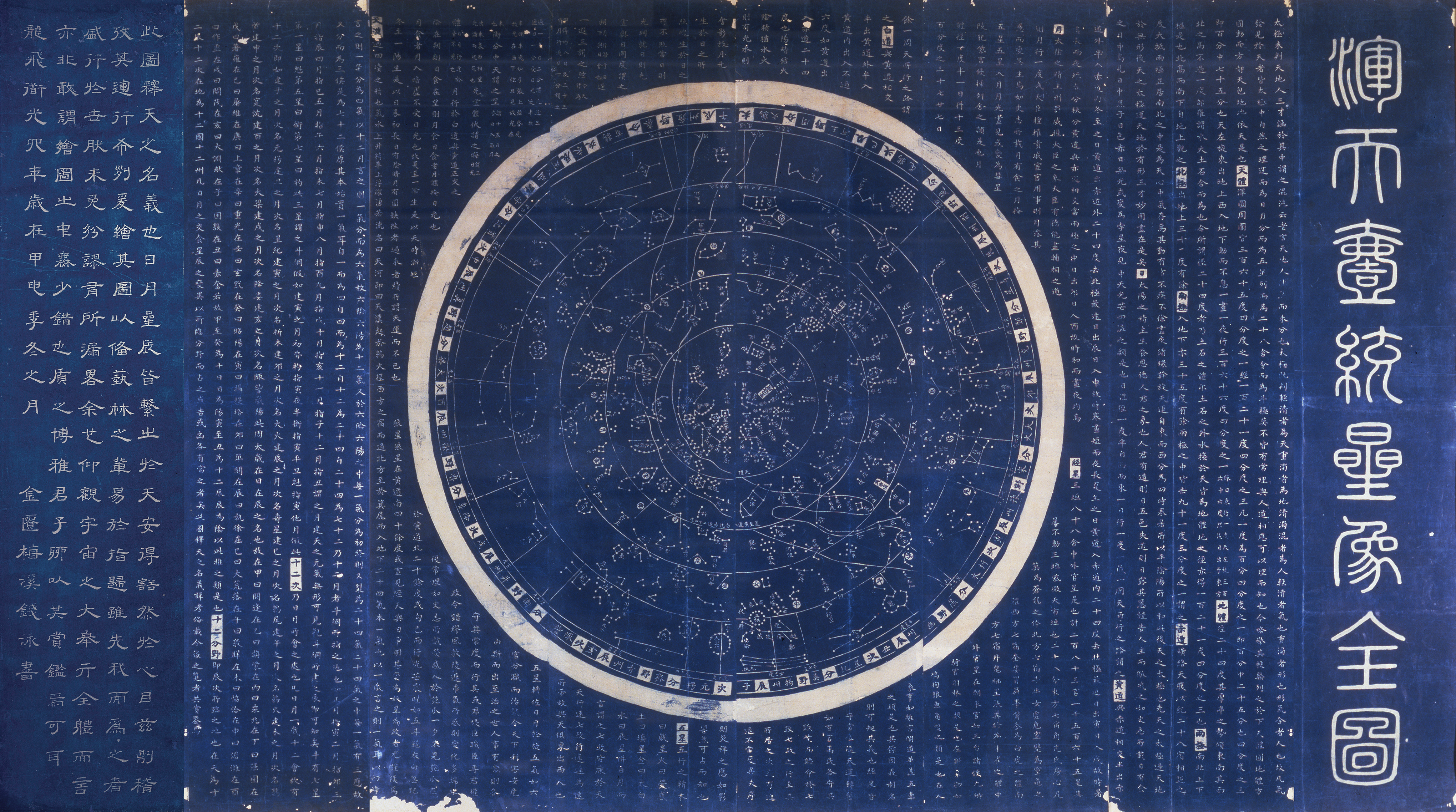

In this blue celestial chart, printed in 1826, most of the body text is identical to that on the Celestial Chart rubbing (天文圖 Tianwen tu) from 1247. On the planisphere, however, constellations have been updated with additional stars discovered by Europeans. These discoveries, made possible by the invention of the telescope, were introduced into Chinese star charts by Europeans working in the Chinese court from the seventeenth century onwards. The curved course of the Milky Way (天河 tianhe, or “heavenly river”) is clearly indicated.

The outer ring of the blue chart marks the horizon, and directly connects the celestial realm with the terrestrial one. It reads counterclockwise, just as the night sky rotates when seen by an observer on earth, and includes numerous directional signifiers. For example, the section at the bottom of the chart with the “first” branch (子 zi) is in the 元枵 yuanxiao position, corresponding to the ancient state of Qi 齊and Qingzhou 青州 province (today’s Shandong 山東 province). This is one of many indications that specific sets of constellations are tied to the ancient twelve provinces of China. The horizon band provides astrological cues and emphasizes the intended functionality of correlations and correspondences between heaven and earth.

Catalog essay

The blue Huntian yitong xingxiang quantu (Complete chart of unified star configurations in the heavens) are star charts with related celestial information. The first (far right) sheet presents the title in seal script while the last (far left) sheet presents an epilogue, a date and a signature of the maker in clerical script. The remaining six sheets present a planisphere and related celestial information using standard script.

The main text body on the 1826 editions of the blue charts essentially copies the text of the 1247 Tianwen tu stele (see entry 2). The sections are clearly indicated by headings, presenting the Chinese characters in blue on white, while the primary text is white on a blue field; the same aesthetic found on the terrestrial maps.

The central and most eye-catching part of this chart is the planisphere. On it, each constellation is named and the curved course of the Milky Way (labeled as Tianhe 天河, “heavenly river”) is clearly demarcated.1 The outer ring (horizon) of the blue charts provides pointers to understanding the night sky and even more directly connects the celestial realm with the terrestrial one. It reads counterclockwise (in the manner of the rotation of the night sky to an observer on earth) and indicates numerous directional signifiers, as also found on the 1247 Tianwen tu. The chart is printed in such a way that the characters always face outward. When the planisphere is “rotated” (conceptually as the physical object is too large) to the time of observation the characters at the “bottom” are always right side up and in a position to be easily read. They are rather technical and require an astronomical and astrological knowledge base. The directional signifiers include the relative widths of the twenty-eight lunar mansions, the twelve terrestrial branches (chen 辰), twelve Jupiter positions or zodiacal positions (ci 次), and the corresponding states and provinces under the astral allocation system (fenye 分野, also known as field-allocation). This division into twelve parts under the astral allocation system had been in astrological use since the late fifth century BCE and correlates celestial and terrestrial space.

For example, the section at the bottom of the chart with the “first” branch zi 子 (north), is in the yuanxiao 元枵 position, corresponding to the ancient state of Qi 齊 and Qingzhou province 青州 (today’s Shandong province, see entry 2). This horizon band of the blue charts provides astrological cues and emphasizes the intended functionality of correlations and correspondences between heaven and earth that are to be interpreted by man. The blue charts, like the Tianwen tu, clearly indicate that specific sets of constellations are tied to the ancient twelve provinces of China. A direct correlation between heaven and earth is thus embedded into the chart itself. This conceptual consideration can be further applied to the overall framing of the combined two blue map and chart, which are created as a pair, terrestrial and celestial, and modeled on the 1247 dili tu and tianwen tu, maintaining the correlative properties between heaven and earth, within a Chinese cultural sphere.

The final sheet (missing on the Adler copy) has an epilogue that simply states the purpose of the map: To explain heavenly bodies. It is dated May 1826 (sixth year of Daoguang reign, fourth month 道光六年歲在丙戊孟夏之月) and signed by Qian Yong from Jingui 金匱梅溪钱泳書. Of all the ten editions of the terrestrial map and the four editions of the celestial map this is the final and only edition that has a signature of a known maker for the blue maps and charts. Qian Yong was a poet and author as well as an accomplished calligrapher of the so-called stone stele (bei 碑) school of calligraphy, traveling extensively around China collecting samples of rubbings from stele. That the celestial chart was designed with multiple styles of calligraphy suggests a calligrapher, like Qian Yong, designed the text layout and that he participated in the creation of all four editions. That the production of all the maps and charts are done in the manner of rubbings suggests a collector of rubbings suggested this method. And that the two stele that the blue map and chart are modeled after were, and still are, found in the city of Suzhou and the blue maps and charts were all produced in the city of Suzhou suggests that Qian Yong participated in all phases of production.

-

In many cases the constellations are updated on the blue charts in comparison to the 1247 chart with additional stars discovered by Europeans (since the discovery of the telescope) and introduced into Chinese star charts by Europeans working in the Chinese court from the seventeenth century onwards. ↩︎