People settle down and move while making communities in ingenious ways. Finding the cultural context and community stories in urban atlases often means reading them slightly against the grain. Over decades, the maps can show how people breathed life into the city.

RADIATING FROM JOY STREET: AFRICAN MEETING HOUSE

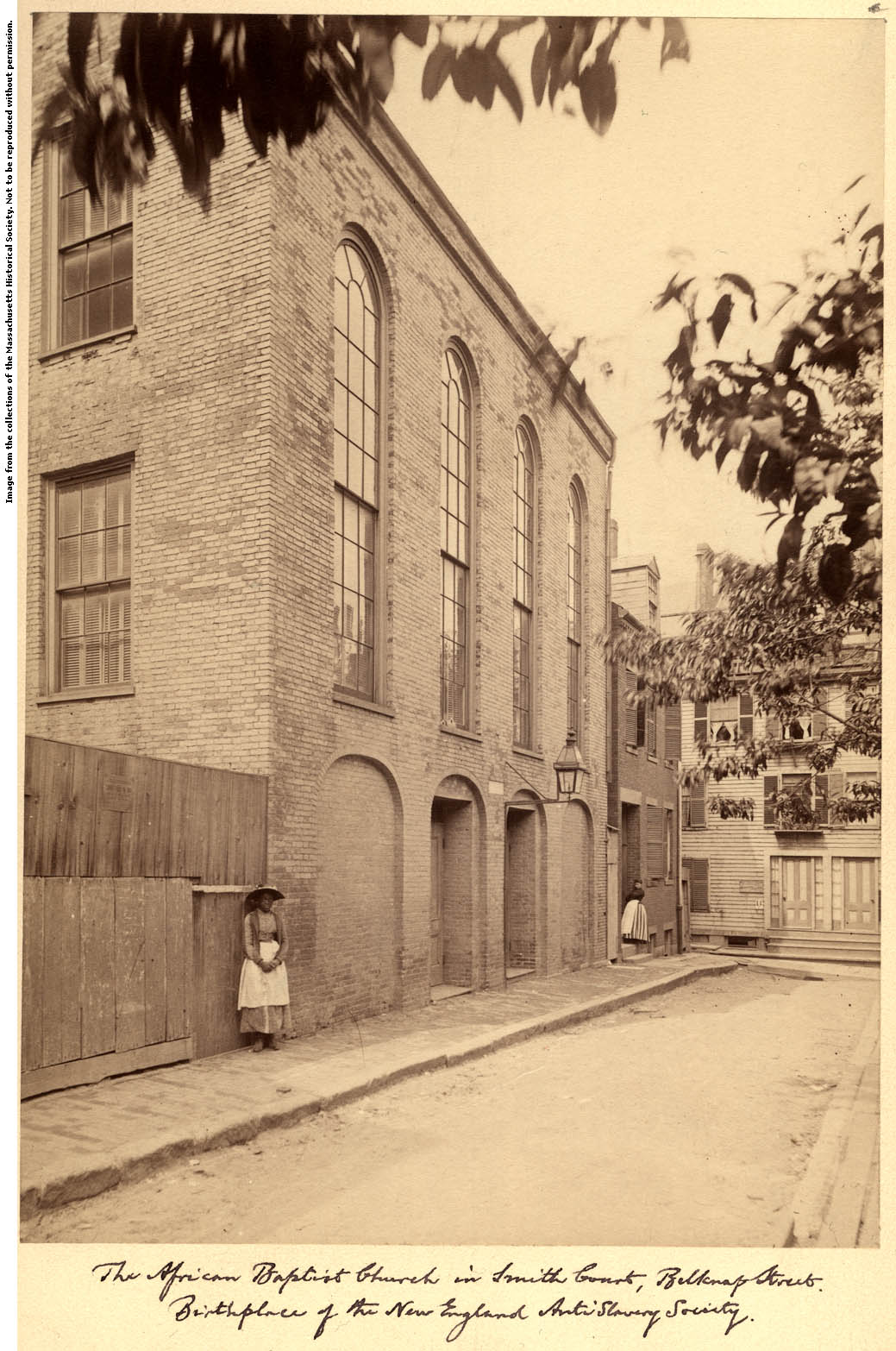

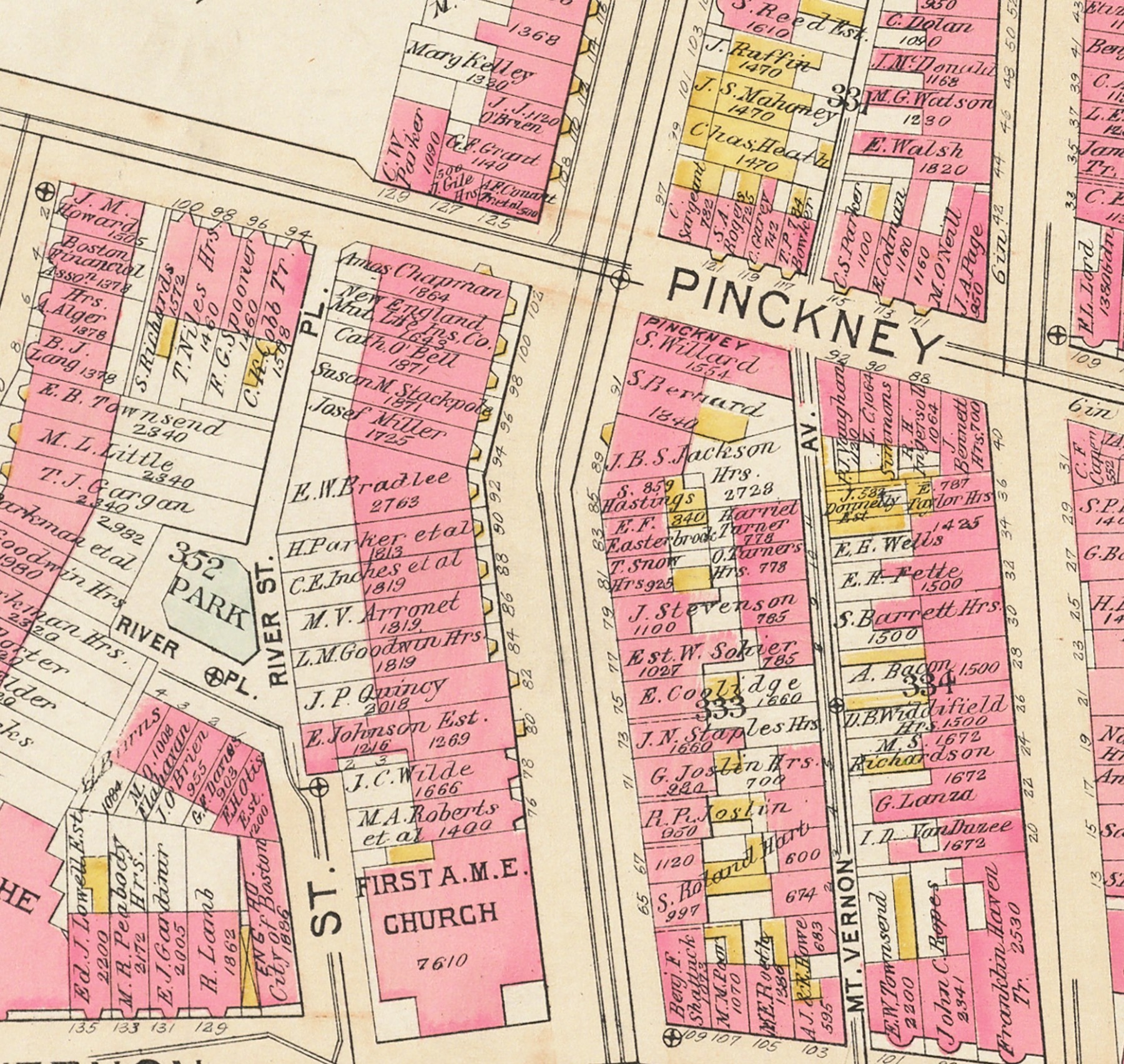

You might not guess just from looking at this 1883 Bromley atlas, but the brick building tucked away at 4 Smith Court off of Joy Street was built by Black artisans in 1806. And while the building is labelled (“Colored Baptist Church,” A) this name only captures one moment in this building’s history. This was the site of the country’s first African Meeting House, which brought together people of all backgrounds and became a gathering place for abolitionists before the Civil War. By 1883, when this atlas was published, the country was emerging from a period of intense activity which saw war and emancipation. The church still served as a meetinghouse for Black Bostonians in a part of Beacon Hill which the African American community had made into an epicenter of public engagement.

Atlas of the city of Boston, city proper, plate F

G.W. Bromley & Co.

1883

Leventhal Map & Education Center

African Meeting House, Boston, Massachusetts

[ca. 1892]

Massachusetts Historical Society

Detail of Atlas of the city of Boston, Boston proper and Back Bay, plate 3

G.W. Bromley & Co.

1928

Leventhal Map & Education Center

Exterior view of the African Meetinghouse, Boston, Mass., 1935

Arthur C. Haskell

1935

Historic New England

Interior view of the African Meeting House, Boston, Mass.

Arthur C. Haskell

undated

Historic New England

The atlases trace the building and movement of communities in late nineteenth century Boston. As changes in employment, transportation, and land values shifted the possibilities and pressures of residential geography, the centers of gravity for some communities migrated from historic core neighborhoods to more peripheral areas. At the tail end of the 1880s, some members of Beacon Hill’s Black community had begun moving to the South End.

In the below crop the (B the African Meetinghouse building) was a community center in the form of a synagogue, reflecting Jewish migration to Beacon Hill by the end of the century.

A change in the patterns of development is visible by comparing different years of atlases. Along Joy Street and Smith Court, there are fewer yellow buildings with an “X” cross—which indicated wooden stables or sheds—and an increase in brick row houses denoted by pink.

In 1972, the Museum of Afro-American History acquired the building and in 2004, restored it to its 1855 interior. Transcending the maps, a landmark of extraordinary endeavor radiates outward from Joy Street.

DRAWING AND ERASING LINES: ROXBURY CROSSING

Roxbury was annexed to Boston in 1868. Urban atlases from those years show a sparsely populated area to the west of Tremont Street heading into the core of present-day Nubian Square. Etching in and erasing streets created outlines for neighborhood blocks in this area, visible in the symbolic language of the atlases through dashed lines or written notes, as seen at the top of the page.

FILLING THE PAGE

There is more to this drawing process than pencil marks. Who designs and defines a neighborhood? The small scale of the atlases provide insight into this question of community formation. In this 1885 Sanborn plate, there are a few more wooden structures emerging on the blank sheet, a sewer covered by a street and several businesses, but there is not yet a discernible neighborhood. One interesting community structure— (A a First Dutch Baptist Church)—sits among the activity. Around the church, streets are being laid out, with a block starting to form that will eventually become a dense residential area.

Roxbury came into its own as a historically Black neighborhood spurred on by the arrival of Southern Blacks to Boston during the Great Migration, as well as pressures from urban development and racist exclusion, which limited Black residents to a few limited choices of neighborhood locales.

Further attempts to redefine the neighborhood from outside are evident in the 1971 plan of Campus High School Redevelopment when Roxbury was marked for urban renewal programs that dramatically shaped much of Boston’s post-war urban fabric—and often disrupted the textures of communities that had previously coalesced in the sites marked for large-scale clearance.

In the 1915 Bromley the same building is a (B synagogue) and it anchors a small, pyramid-shaped block containing a fire house, a bath house, and several wooden residences. By 1931, while the block’s overall density remained largely the same, the occupant of this building became an (C African Methodist Episcopalian church).

(34) (35)

Detail of Insurance map of Charlestown, portions of Roxbury (now annexed to Boston) and Cambridge, plate 25

D. A. Sanborn

1868

Leventhal Map & Education Center

Detail of Insurance maps of Boston, volume two, plate 52

D. A. Sanborn

1885

Leventhal Map & Education Center

Detail of Atlas of the city of Boston, Roxbury, plate 5

G.W. Bromley & Co.

1915

Leventhal Map & Education Center

Detail of Atlas of the city of Boston, Roxbury, plate 5

G.W. Bromley & Co.

1931

Leventhal Map & Education Center

Campus High School urban renewal area Massachusetts R-129 : illustrative site plan

Boston Redevelopment Authority

1971

Boston Public Library Gov Docs

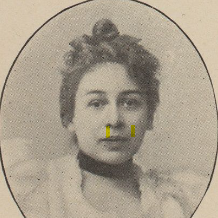

Florida's Story

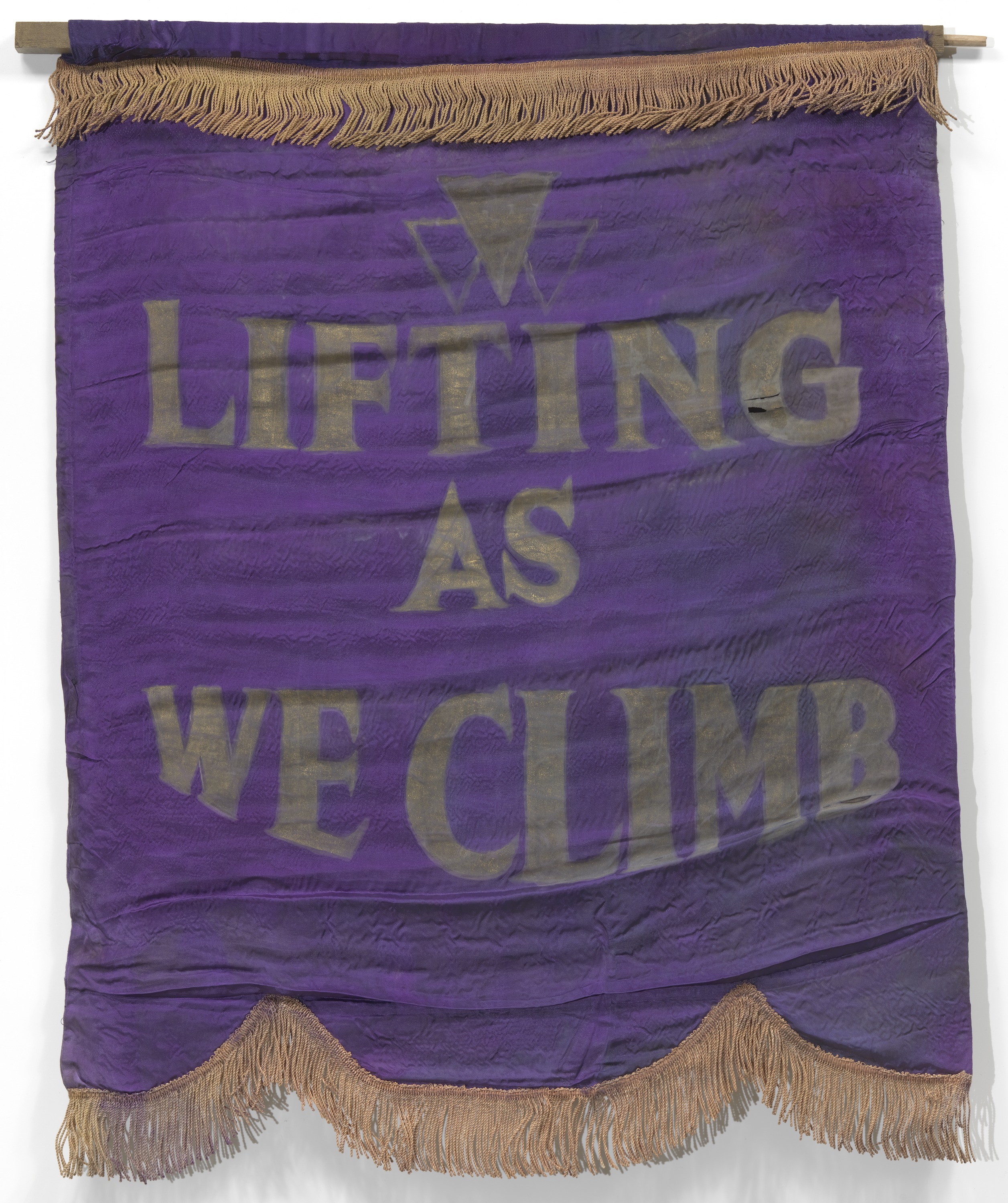

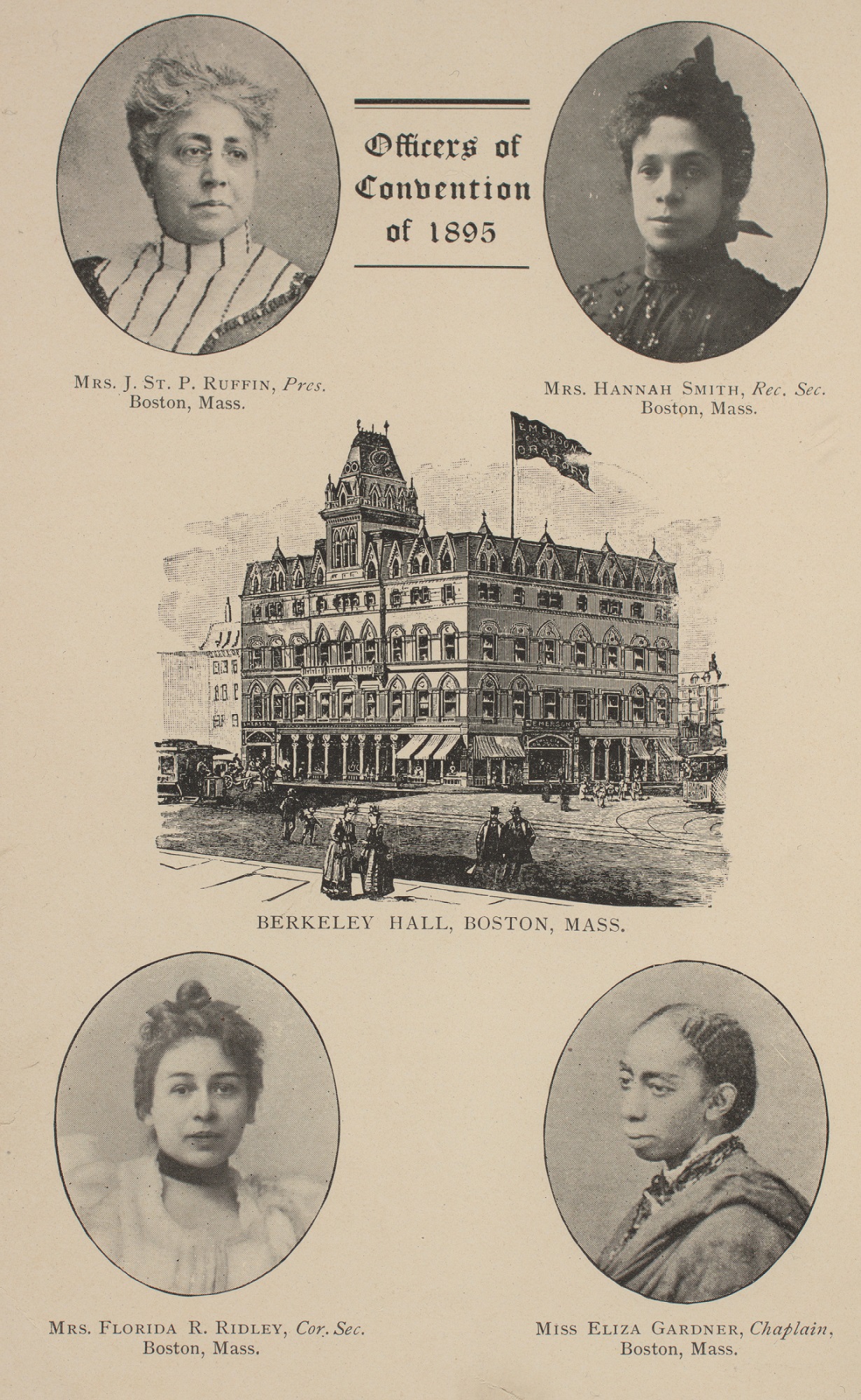

Florida is probably best known for her participation in the Black women’s club movement. As a founding member of the Woman’s Era Club, a Boston-based club started in 1894 by her mother, and later a member of the National Association of Colored Women’s Clubs (NACWC), Florida wrote and organized around issues of the day—from promoting the arts to women’s suffrage. The club movement created a national community of women committed to promoting the well-being of Black people, with a particular emphasis on Black women. The motto of the NACWC was “Lifting as We Climb” to convey its dedication to racial uplift.

‘Women’s clubs are helping to bring us to a recognition of the truth that true dignity does not need barriers in order to preserve itself; that snobbishness is a vice, and that while friendship should be bound by congeniality, neighborliness should know no bounds. The club means the spirit of neighborliness with the world, the recognition of our duty toward our neighbor, and not only of our common humanity but our common divinity; the club helps us not only to make the best of that within us but to see the best of that in others.”

—Florida Ruffin Ridley, Woman’s Era, Oct-Nov, 1896

In 1895, Florida and her mother were principal organizers of the first national convention of Black women’s clubs. The convention was held in Boston in Berkeley Hall, also known as the Odd Fellows Hall. Women from 14 states gathered to form a national organization. They created committees to address issues such as lynching, convict leasing, segregation and temperance, and listened to speeches from national leaders, Black and white, such as Booker T. Washington and William Lloyd Garrison, Jr. The convention then moved to the Charles Street Church to finish their organizing, just a block from the Ruffin home.

“Our woman’s movement is woman’s movement in that it is led and directed by women for the good of women and men, for the benefit of all humanity, which is more than any one branch or section of it. We want, we ask the active interest of our men, and, too, we are not drawing the color line; we are women, American women, as intensely interested in all that pertains to us as such as all other American women. We are not alienating or withdrawing, we are only coming to the front, willing to join any others in the same work and cordially inviting and welcoming any others to join us.”

—Address of Josephine St. P. Ruffin to the National Conference of Colored Women, Boston, 1895

WHO BRINGS YOUR COMMUNITY TOGETHER, AND FOR WHAT PURPOSES? IN WHAT WAYS DO YOU CONTRIBUTE TO CREATING A STRONG COMMUNITY?

IMMIGRANT ICONS OF A WORKING CLASS NEIGHBORHOOD

The borders of a neighborhood might not change dramatically over a long period. Instead, transformation occurs at the scale of individual people and families as they repurpose urban space to strengthen communal ties, start businesses, establish social networks, and weave patterns of daily life.

This portion of the South Cove neighborhood, which was filled in from salt flats in the 1830s, became a hub of Syrian, Greek, Irish and Chinese communities at the turn of the century before eventually consolidating into what we now know as Chinatown. Looking at details in South Cove provides clues as to how different immigrant communities left their mark on the working class neighborhood.

The area has a strong block appearance which defines the neighborhood as a dense grid with commercial structures on ground floors, and residences above.

Detail of Atlas of the city of Boston, Boston proper and Back Bay, plate 14

G.W. Bromley & Co.

1902

Leventhal Map & Education Center

South side of Beach Street, east corner of Tyler Street, Boston, Mass., 1901

1901

Historic New England

Corner of Kneeland and Hudson Streets, Looking South, 10:50 A.M.

Elmer Chickering

1901

Boston College

On the far left there is a (Syrian Greek Orthodox Church) (”G. O. Ch.”), just a few buildings farther down from the public playground. (The Denison House), which was part of the College Settlement Movement, a charitable reform effort to help poor and immigrant communities, was located on 93 Tyler Street.

Detail of Atlas of the city of Boston, Boston proper and Back Bay, plate 14

G.W. Bromley & Co.

1917

Leventhal Map & Education Center

Massachusetts. Boston. New municipal building. Oak and Tyler Sts.

[ca. 1908–1925]

Boston Public Library Arts Department

On the block to the left of the plate, above Tyler Street, a playground has appeared next to a (municipal building), which featured a branch library on the first floor. In the middle section, there are gray X’s penciled in by the owner of this copy of the atlas, indicating buildings which had been demolished. Nearby, at 68 Hudson Street across from the Quincy School, is a Syrian Roman Catholic Church.

Detail of Atlas of the city of Boston, Boston proper and Back Bay, plate 14

G.W. Bromley & Co.

1928

Leventhal Map & Education Center

By the 1980s, economic investment following urban renewal stimulated efforts to visually represent the Chinese heritage of the neighborhood. In 1982, Taiwan donated the China Trade Gate, designed by David Judelson, to span Beach and Hudson Streets. This 1989 sketch by the Boston Redevelopment Authority marks certain buildings in the area as simply “Chinese” among several other—more nuanced—Western styles such as “High Victorian Gothic” or “Greek revivalist,” which refers to classical architecture rather than the Greek immigrant community.

Numbers 74 through 84 Kneeland Street, Boston, Mass., January 3, 1927

W. W. K. Campbell

1927

Historic New England

Detail of Atlas of the city of Boston, Boston proper and Back Bay, plate 11

1922

Leventhal Map & Education Center

Chinatown architectural styles

Boston Redevelopment Authority

1989

Leventhal Map & Education Center