Waging War

The word “propaganda,” which literally means “something to be spread,” typically refers to public information produced by a government in order to convince people to act or think in a certain manner. While we tend to think of propaganda as inherently deceitful and over-the-top, most propaganda takes the form of news and bulletins, bent towards the perspective of a government eager to make things look like they are going its way. When a war is ongoing, the authorities become even more anxious to control the spread of information and eager to whip up patriotic sentiment.

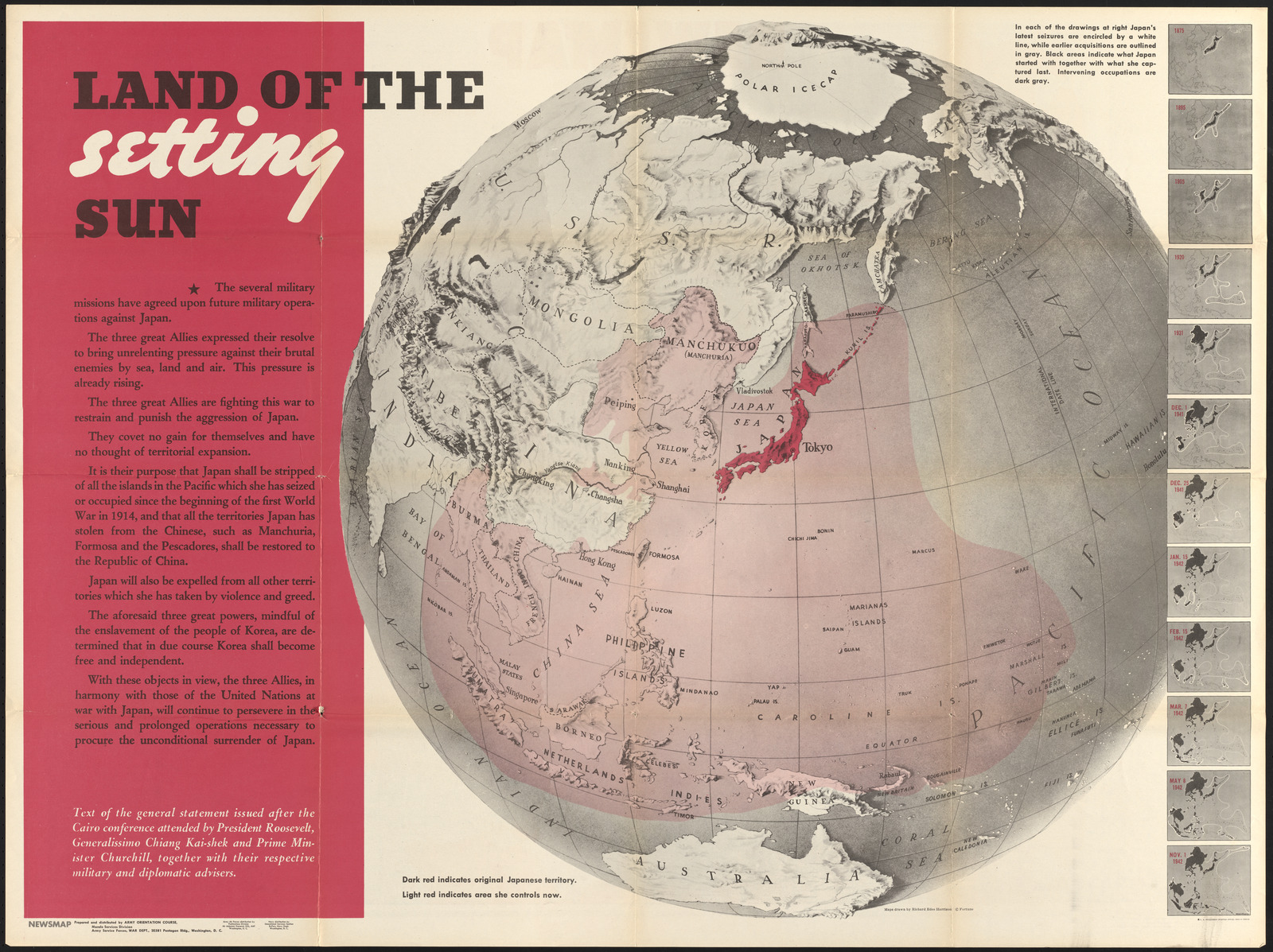

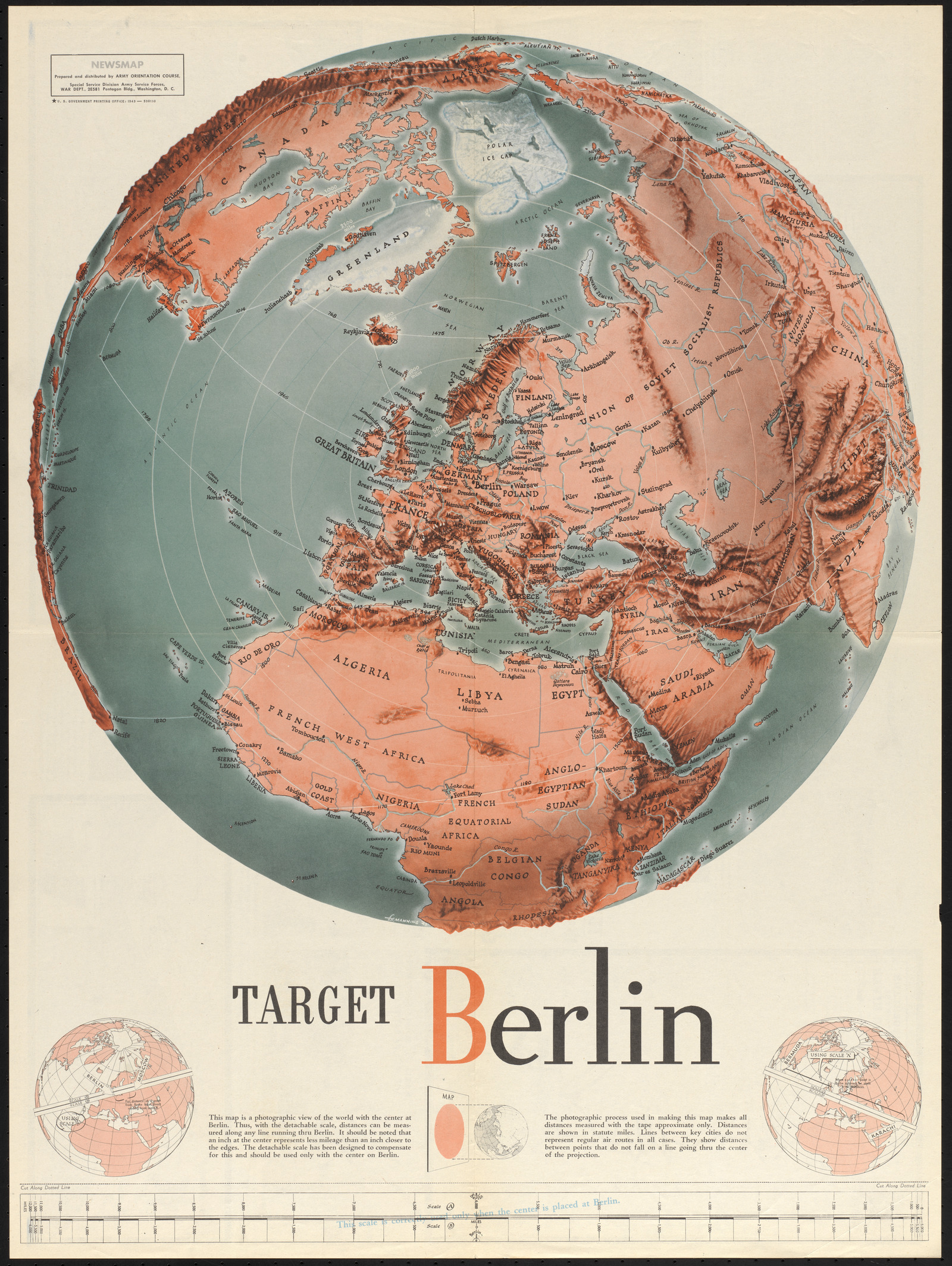

During World War II, the United States narrated the war from its point of view in the weekly publication Newsmap, which wove together maps, photographs, and reports from the front into a patriotic message about the war effort. These maps would have been displayed in post offices, schools, and other public spaces, in order to instruct Americans in the official picture of the war effort. As government depository materials, they were sent to libraries and formed a daily register of how the U.S. military saw both itself and the rest of the world.

This 1943 Newsmap,with a global view created by Richard Edes Harrison, shows a timelapse series of the Japanese Empire's expanding reach into the Pacific. Set against that spread outward was a promise that the war would see the eventual “setting” of the Japanese sun as the Allied forces begin their campaigns. The color and language dramatize the scale and significance of the threat while also offering a reassuring narrative about the power of the Allied war effort.

In another 1943 Newsmap, titled “Target Berlin,” the view pivots so that the globe is centered on the bullseye of the European Front campaign against Nazi Germany. This map includes an exercise in projection and distance measuring, with a scale ruler that could be cut out and pivoted around the enemy capital. Azimuthal projections, like this one, create concentric circles of equal distance around their center point, the kinds of direct routes that could be traversed by airplanes following a “great circle” without having to stop for mountains or rivers. This map showed that places like Iceland were just as close to Berlin as were the farthest points of mainland Europe.