In the first installment of this series, Time Travel Back to 1906 Boston, we glimpsed what Boston was like when Billy Bitner rode through the streets filming scenes of daily life. Here we’ll hop onboard the streetcar and accompany him on his journey.

Starting Downtown

We begin on Tremont Street traveling toward Boston Common. The small building at the southeast corner on the Common is the Boylston subway station, which at the time was less than ten years old. Many of the surrounding buildings had been erected over the previous decade, including the Masonic temple, which is on the corner to the left as we turn onto Boylston. The building on the right is a hotel, but a century earlier that site had been the location of John Quincy Adams’ home.

Riding east down Boylston Street, we see a sign for Washburn’s Department Store, with a smaller one saying they offer clothes on credit. Next to the commercial signage, we see a three-dimensional plaque with a tree. That marks the location of the Liberty Tree, the site of a gathering of the Sons of Liberty in pre-Revolutionary Boston. The building and tree marker are still there, though Washburn’s is long gone.

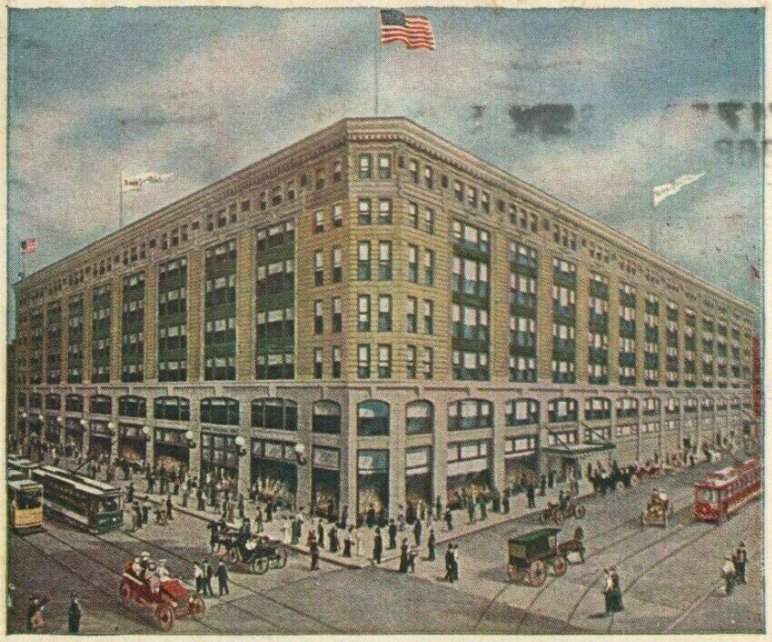

Siegel’s (note lamps on left) (1)

Boylston Street ends at Washburn’s and we turn left onto Washington Street, downtown Boston’s main commercial thoroughfare for most of its history. On the right our attention is drawn to a row of large globular light fixtures sticking out from the building. That’s Siegel’s department store. The building was brand new, and it was huge, 450,000 square feet (a typical Home Depot is about 100,000). Over three thousand people worked there. Modern escalators whisked people from floor to floor, but they seem to have created some confusion. When the store first opened, employees had to be stationed at the top and bottom of each escalator to provide guidance for customers who thought they were supposed to sit on the steps (2). Watch carefully as we pass Siegel’s and on the next building you’ll see the sign for the shop where Cushing sold his medicinal wines.

Notice the crowds everywhere. A clock further down the street shows 1:00 p.m. and it seems everyone is out shopping. Stores typically weren’t open evenings at the time. A sign at the corner of Washington Street and Temple Place proclaims it to be “The Busiest Corner on Boston’s Busiest Street.”

Going down Washington Street we pass the venerable Jordan Marsh department store, New England’s largest. Then we pass a waiting automobile with a circular radiator. It looks like a 1906 National, the company’s slogan was “Watch for the Round Radiator.” With an advertised price of $3,000, it wasn’t for everyone. Henry Ford’s Model T was still two years in the future.

Over to North Station

After turning the corner at Old South, the movie jumps ahead to the North Station area (3), where we find ourselves looking at a blank wall with a few people walking by. One wonders why so much time is focused on that wall.

Perhaps it was the elevated train at the rear that the filmmakers wanted to show. Though Boston had been first in the country with subway service, it was late to the game with elevated rail (4). Boston’s first elevated trains had just been placed in service in 1901, so to viewers in 1906 this line would have been evidence of Boston’s push to be at the forefront of rapid transit. And the uninteresting blank wall concealed the end station and turnaround for the subway. Finally, the building at the end of the street is the new North Station, and we, of course, are riding in a surface streetcar. Thus, this seemingly mundane scene depicts the nexus of four modes of mass transit.

Turning onto Causeway Street, we see passengers waiting outside the station, which at the time was called North Union Station. This indicated that the station was served by multiple railroads. A post office is connected to the station, which makes sense since intercity mail would have travelled by rail.

To Summer Street and South Station

Jaynes 1898 Price List (5)

After traveling down some bustling streets, we turn left onto Summer Street in front of Jaynes Annex. Jaynes was Boston’s leading drugstore. Its 1898 Price List included recipes by Fannie Farmer for every season of the year. In addition, it featured ads for such enticing products as Jaynes’ Magic Insect Powder (If it does not KILL the bugs we will refund the money) and Jaynes’ Castormels (A Pleasant Laxative Confection) (6).

This area is at the heart of the swath of downtown Boston destroyed by the fire of 1872. There are signs for shoe stores and footwear-related businesses. Boston was the center of U.S. shoe manufacturing, and the area to the right was known as the Leather District.

South Station Complex (7)

After passing beneath another set of new elevated tracks, we find ourselves at South Union Station, which to Bostonians of the day was probably the most important place seen in the entire film. Opened in 1898, it was touted as the largest railway station in the world. The map at the left shows how critical this was to the city’s economic life. While the tracks connected Boston to the rest of the country, the piers at the left, connected it with the rest of the world, crucial at a time when international travel, both passenger and freight, was exclusively by sea.

To Back Bay

The movie then jumps again, this time to Boylston Street in the Back Bay. Much of the neighborhood was residential, but Boylston Street was home to cultural institutions and some businesses. Fifty years earlier this entire area had been under water.

The first thing we notice is that we are no longer in a congested district—the streets have plenty of room for both pedestrians and vehicles. The first two buildings we see are the original home of M.I.T. The university wouldn't move to Cambridge until 1917. The next block is home to some hotels, businesses, a church and a school. Within a few years, this part of Boylston Street would become Boston’s center for the burgeoning new automobile business.

Boston Public Library (The statues of Art and Science that currently flank the entrance had not yet been installed) (8)

As the streetcar begins to turn left onto Huntington Avenue, we see buildings that remain Copley Square landmarks. The Old South Church with its bell tower is on the right and the then new (1895) Boston Public Library on the left. The tall building the behind the library is the Lenox Hotel, which remains in business at the same location. The building between the library and hotel is the Harvard Medical School. Later that year, it would move to its current Longwood Avenue campus.

Had the camera panned to the left, we could have seen the original home of the Museum of Fine Arts. It moved down Huntington Avenue to its current location three years later.

Our journey ends a couple blocks up Huntington Avenue in front of the Copley Square Hotel at the corner of Exeter Street, which still exists. The empty lot on the right was a railway yard, and the building in front of us on the left is Mechanics Hall, which served as an auditorium and convention center until it was demolished in 1959. Both spaces are now part of the Prudential Center development, built in the 1960s.

At first glance, the world of 1906 seems quite remote from our own. But look more closely and you’ll see things really weren’t all that different—some people appear to have been in a hurry, others not; some were outfitted in the latest fashion, others more modestly; some were conversing amicably with their companions, others seemingly wished to be left alone.

The 1906 Bostonians we see were running errands, going to appointments and meeting friends. Their clothes and accents might have been different from ours, but their hopes and dreams may have been strikingly familiar to us today. Plus ça change, plus c'est la même chose … the more things change, the more they stay the same.

Notes

1: Detail from postcard, Henry Siegel Co., Henry Siegel Co.’s New Store, Boston, Mass. (c. 1910), https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.phptitle=File:Henry_Siegel_Co_WashingtonSt_EssexSt_Boston_ca1910s.png&oldid=866343667

2: Siegel’s New Store Opened, The Boston Globe, p. 4 (September 12, 1905).

3: If the filming was done in a single session and they went directly from one site to the next, the streetcar passed right by the Old State House and Faneuil Hall, neither of which is included, lending support to the speculation that the filmmaker was not trying to portray historic Boston.

4: New York’s “El” began service in 1878, Sonia Kahn, What Goes Up Must Come Down: A brief history of New York City’s elevated rail and subway lines, Library of Congress (May 19, 2022), Library of Congress web site, https://blogs.loc.gov/maps/2022/05/what-goes-up-must-come-down-a-brief-history-of-new-york-citys-elevated-rail-and-subway-lines/.

5: Jaynes & Co., 1898 Price list of Drug Store Goods, from the Winterthur Museum Library, https://archive.org/details/pricelistofdrugs00jayn. https://archive.boston.com/news/local/massachusetts/articles/2009/10/13/a_century_ago_boston_led_the_way_in_taming_the_states_wild_roads/.

6: You can download the Price List from the Internet Archive. https://archive.org/details/pricelistofdrugs00jayn

7: Geo. H. Walker & Co., View of Boston freight terminals, the New York, New Haven & Hartford Railroad, Norman B. Leventhal Map & Education Center (1903), https://collections.leventhalmap.org/search/commonwealth:df65xz27g

8: Screen capture from Seeing Boston.

Our articles are always free

You’ll never hit a paywall or be asked to subscribe to read our free articles. No matter who you are, our articles are free to read—in class, at home, on the train, or wherever you like. In fact, you can even reuse them under a Creative Commons CC BY-ND 2.0 license.