Your New Washington Park: A Bold Program in Urban Renewal

Boston Redevelopment Authority

1963

Boston Public Library

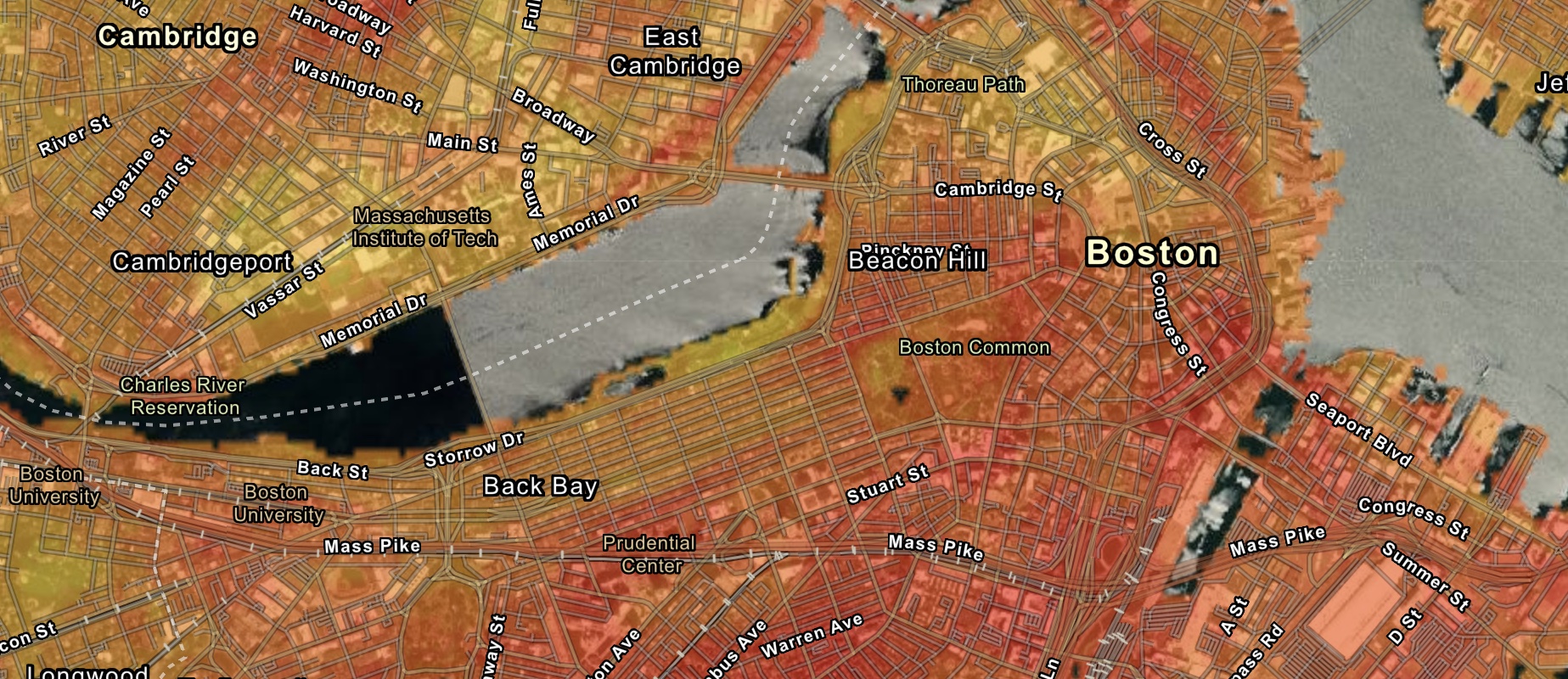

By the middle of the twentieth century, the term “blight” had become a catch-all description for the combination of environmental and social challenges facing major cities. The image of urban blight oftentimes referred to the landscape of older areas built during the industrial period, marred by dilapidated or abandoned buildings and ill-kept public spaces. But many observers also invoked blight as a term to describe groups of people at the bottom of the social and economic order. Government programs to improve the living conditions in cities therefore sought to both redesign the physical layout of urban areas and also manage the populations living in them. This 1963 pamphlet was published by the Boston Redevelopment Authority (BRA) to share its vision for urban renewal in the Washington Park area of Roxbury. The inclusion of both social infrastructure like schools and housing together with environmental upgrades like new playgrounds and street trees marked a comprehensive effort to reorder the human landscape. Like many plans of this era, it relied on an abstract map view to show the overall shape of the interventions.

Clean-up, Paint-up

Freedom House

[ca. 1955]

Northeastern University Libraries

Let’s Get M.A.D. and Clean Up Washington Park: Your Guide to Action

Freedom House

[ca. 1965]

Northeastern University Libraries

One of the civic groups which most eagerly advocated for urban renewal in Roxbury was Freedom House, founded by the Black reformers Otto and Muriel Snowden. These community bulletins published by Freedom House in the 1950s and 1960s show how the organization saw itself as a steward of Roxbury’s urban environment. Urging neighborhood residents to clean up their community and report hazards such as derelict cars, such efforts sprang from a belief that a well-ordered environment could help fend off the blight that was spreading throughout the city. Freedom House realized that cosmetic improvements were not enough to undo the combination of racial and class oppression which hung over Boston’s Black community, and so they also helped to steer the public investments and planning power of urban renewal towards Roxbury. The organization’s close relationship with the BRA led more radical activists to question the value of large-scale, top-down redevelopment projects.